|

Eliminate barriers to practice.

There are many things that can get in the way of practice, which makes it much more difficult to acquire any skill. Relying on willpower to consistently overcome these barriers is a losing strategy. We only have so much willpower at our disposal each day, and it’s best to use that willpower wisely. The best way to invest willpower in support of skill acquisition is to use it to remove these soft barriers to practice. By rearranging your environment to make it as easy as possible to start practicing, you’ll acquire the skill in far less time. Make dedicated time for practice. The time you spend acquiring a new skill must come from somewhere. If you rely on finding time to do something, it will never be done. If you want to find time, you must make time. You have 24 hours to invest each day: 1,440 minutes, no more or less. You will never have more time. If you sleep approximately 8 hours a day, you have 16 hours at your disposal. Some of those hours will be used to take care of yourself and your loved ones. Others will be used for work. Whatever you have left over is the time you have for skill acquisition. If you want to improve your skills as quickly as possible, the larger the dedicated blocks of time you can set aside, the better. The best approach to making time for skill acquisition is to identify low-value uses of time, then choose to eliminate them. As an experiment, I recommend keeping a simple log of how you spend your time for a few days. All you need is a notebook. The results of this time log will surprise you: if you make a few tough choices to cut low-value uses of time, you’ll have much more time for skill acquisition. The more time you have to devote each day, the less total time it will take to acquire new skills. I recommend making time for at least ninety minutes of practice each day by cutting low-value activities as much as possible. I also recommend precommitting to completing at least twenty hours of practice. Once you start, you must keep practicing until you hit the twenty-hour mark. If you get stuck, keep pushing: you can’t stop until you reach your target performance level or invest twenty hours. If you’re not willing to invest at least twenty hours up front, choose another skill to acquire. Mastery by Robert Greene This opportunistic bent of the human mind is the source and foundation of our creative powers6/26/2013

The animal world can be divided into two types—specialists and opportunists. Specialists, like hawks or eagles, have one dominant skill upon which they depend for their survival. When they are not hunting, they can go into a mode of complete relaxation.

Opportunists, on the other hand, have no particular specialty. They depend instead on their skill to sniff out any kind of opportunity in the environment and seize upon it. They are in states of constant tension and require continual stimulation. We humans are the ultimate opportunists in the animal world, the least specialized of all living creatures. Our entire brain and nervous system is geared toward looking for any kind of opening. This opportunistic bent of the human mind is the source and foundation of our creative powers, and it is in going with this bent of the brain that we maximize these powers. Mastery by Robert Greene Researchers at Stanford University discovered in the 1970s that one of the best ways to combat negative distractions is simply to embrace positive distractions. In short, we can fight bad distractions with good distractions.

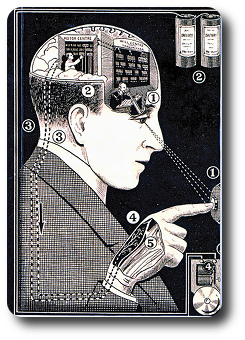

In the Stanford study,7 children were given an option to eat one marshmallow right away, or wait a few minutes and receive two marshmallows. The children who were able to delay their gratification employed positive distraction techniques to be successful. Some children sang; others kicked the table; they simply did whatever they needed to do to get their minds focused on something other than the marshmallows. There are many ways to use positive distraction techniques for more than just resisting marshmallows. Set a timer and race the clock to complete a task. Tie unrelated rewards to accomplishments—get a drink from the break room or log on to social media for three minutes after reaching a milestone. Write down every invading and negatively distracting thought and schedule a ten-minute review session later in the day to focus on these anxieties and lay them to rest. Still, it takes a significant amount of self-control to work in a chaotic environment. Ignoring negative distractions to focus on preferred activities requires energy and mental agility. For his book Willpower, psychologist Roy Baumeister analyzed findings from hundreds of experiments to determine why some people can retain focus for hours, while others can’t. He discovered that self-control is not genetic or fixed, but rather a skill one can develop and improve with practice. Baumeister suggests many strategies for increasing self-control. One of these strategies is to develop a seemingly unrelated habit, such as improving your posture or saying “yes” instead of “yeah” or flossing your teeth every night before bed. This can strengthen your willpower in other areas of your life. Additionally, once the new habit is ingrained and can be completed without much effort or thought, that energy can then be turned to other activities requiring more self-control. Tasks done on autopilot don’t use up our stockpile of energy like tasks that have to be consciously completed. Entertaining activities, such as playing strategic games that require concentration and have rules that change as the game advances, or listening to audio books that require attention to follow along with the plot, can also be used to increase attention. Even simple behaviors like regularly getting a good night’s sleep are shown to improve focus and self-control. Manage Your Day-to-Day: Build Your Routine, Find Your Focus, and Sharpen Your Creative Mind (The 99U Book Series) by Jocelyn K. Glei When Leonardo da Vinci wanted to create a whole new style of painting, one that was more lifelike and emotional, he engaged in an obsessive study of details. He spent endless hours experimenting with forms of light hitting various geometrical solids, to test how light could alter the appearance of objects. He devoted hundreds of pages in his notebooks to exploring the various gradations of shadows in every possible combination. He gave this same attention to the folds of a gown, the patterns in hair, the various minute changes in the expression of a human face. When we look at his work we are not consciously aware of these efforts on his part, but we feel how much more alive and realistic his paintings are, as if he had captured reality.

The average person does not generally pay attention to what we shall call negative cues, what should have happened but did not. It is our natural tendency to fixate on positive information, to notice only what we can see and hear. In business, the natural tendency is to look at what is already out there in the marketplace and to think of how we can make it better or cheaper. The real trick—the equivalent of seeing the negative cue—is to focus our attention on some need that is not currently being met, on what is absent. This requires more thinking and is harder to conceptualize, but the rewards can be immense if we hit upon this unfulfilled need. One interesting way to begin such a thought process is to look at new and available technology in the world and to imagine how it could be applied in a much different way, meeting a need that we sense exists but that is not overly apparent. If the need is too obvious, others will already be working on it. Mastery by Robert Greene Author Jonathan Franzen takes the temptation of multitasking so seriously that, to write his bestselling novel Freedom, he locked himself away in a sparsely furnished office. As he told Time magazine, he went so far as to strip his vintage laptop of its wireless card and surgically destroy its Ethernet port with superglue and a saw. He then established a cocoon-like environment with earplugs and noise-cancelling headphones.

A little extreme, perhaps, but Franzen demonstrated shrewd insight into human fallibility. Creative minds are highly susceptible to distraction, and our newfound connectivity poses a powerful temptation for all of us to drift off focus. Studies show that the human mind can only truly multitask when it comes to highly automatic behaviors like walking. For activities that really no such thing as multitasking, only task switching—the process of flicking the mind back and forth between different demands. It can feel as though we’re super-efficiently doing two or more things at once. But in fact we’re just doing one thing, then another, then back again, with significantly less skill and accuracy than if we had simply focused on one job at a time. Manage Your Day-to-Day: Build Your Routine, Find Your Focus, and Sharpen Your Creative Mind (The 99U Book Series)by Jocelyn K. Glei The strategy is simple, I think.

The strategy is to have a practice, and what it means to have a practice is to regularly and reliably do the work in a habitual way. The practice is a big part. The second part of it, which I think is really critical, is understanding that being creative means that you have to sell your ideas. If you’re a professional, you do not get to say, “Ugh, now I have to go sell it”—selling it is part of it because if you do not sell it, there is no art. No fair embracing one while doing a sloppy job on the other. The reason you might be having trouble with your practice in the long run—if you were capable of building a practice in the short run—is nearly always because you are afraid. The fear, the resistance, is very insidious. It doesn’t leave a lot of fingerprints, but the person who manages to make a movie short that blows everyone away but can’t raise enough cash to make a feature film, the person who gets a little freelance work here and there but can’t figure out how to turn it into a full-time gig—that person is practicing self-sabotage. These people sabotage themselves because the alternative is to put themselves into the world as someone who knows what they are doing. They are afraid that if they do that, they will be seen as a fraud. It’s incredibly difficult to stand up at a board meeting or a conference or just in front of your peers and say, “I know how to do this. Here is my work. It took me a year. It’s great.” This is hard to do for two reasons: (1) it opens you to criticism, and (2) it puts you into the world as someone who knows what you are doing, which means tomorrow you also have to know what you are doing, and you have just signed up for a lifetime of knowing what you are doing. It’s much easier to whine and sabotage yourself and blame the client, the system, and the economy. This is what you hide from—the noise in your head that says you are not good enough, that says it is not perfect, that says it could have been better. Seth Godin Manage Your Day-to-Day: Build Your Routine, Find Your Focus, and Sharpen Your Creative Mind (The 99U Book Series) by Jocelyn K. Glei You must let go of your need for comfort and security. Creative endeavors are by their nature uncertain. You may know your task, but you are never exactly sure where your efforts will lead. If you need everything in your life to be simple and safe, this open-ended nature of the task will fill you with anxiety. If you are worried about what others might think and about how your position in the group might be jeopardized, then you will never really create anything. You will unconsciously tether your mind to certain conventions,

We do not like what is unfamiliar or unknown. To compensate for this, we assert ourselves with opinions and ideas that make us seem strong and certain. Many of these opinions do not come from our own deep reflection, but are instead based on what other people think. Furthermore, once we hold these ideas, to admit they are wrong is to wound our ego and vanity. Truly creative people in all fields can temporarily suspend their ego and simply experience what they are seeing, without the need to assert a judgment, for as long as possible. This ability to endure and even embrace mysteries and uncertainties is what Keats called negative capability. All Masters possess this Negative Capability, and it is the source of their creative power. This quality allows them to entertain a broader range of ideas and experiment with them, which in turn makes their work richer and more inventive. Negative Capability will be the single most important factor in your success as a creative thinker. In the sciences, you will tend to entertain ideas that fit your own preconceptions and that you want to believe in. This unconsciously colors your choices of how to verify these ideas, and is known as confirmation bias. With this type of bias, you will find the experiments and data that confirm what you have already come to believe in. The uncertainty of not knowing the answers beforehand is too much for most scientists. In the arts and letters, your thoughts will congeal around political dogma or predigested ways of looking at the world, and what you will often end up expressing is an opinion rather than a truthful observation about reality. To put Negative Capability into practice, you must develop the habit of suspending the need to judge everything that crosses your path. You consider and even momentarily entertain viewpoints opposite to your own, seeing how they feel. You observe a person or event for a length of time, deliberately holding yourself back from forming an opinion. You seek out what is unfamiliar—for instance, reading books from unfamiliar writers in unrelated fields or from different schools of thought. You do anything to break up your normal train of thinking and your sense that you already know the truth. Mastery by Robert Greene “It’s not about ideas, it’s about making ideas happen.”

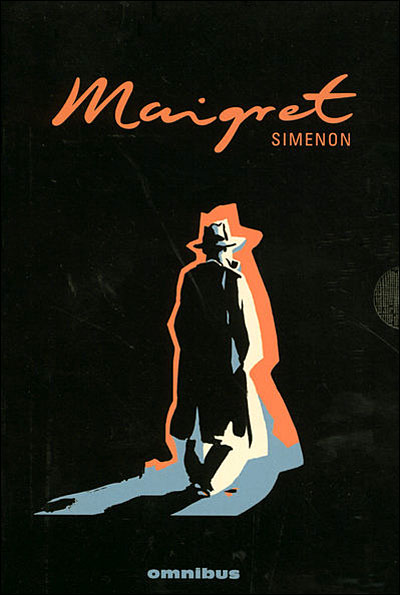

It’s time to stop blaming our surroundings and start taking responsibility. While no workplace is perfect, it turns out that our gravest challenges are a lot more primal and personal. Our individual practices ultimately determine what we do and how well we do it. Specifically, it’s our routine (or lack thereof), our capacity to work proactively rather than reactively, and our ability to systematically optimize our work habits over time that determine our ability to make ideas happen. Through our constant connectivity to each other, we have become increasingly reactive to what comes to us rather than being proactive about what matters most to us. Truly great creative achievements require hundreds, if not thousands, of hours of work, and we have to make time every single day to put in those hours. Routines help us do this by setting expectations about availability, aligning our workflow with our energy levels, and getting our minds into a regular rhythm of creating. At the end of the day—or, really, from the beginning—building a routine is all about persistence and consistency. Don’t wait for inspiration; create a framework for it. CREATIVE WORK FIRST, REACTIVE WORK SECOND The single most important change you can make in your working habits is to switch to creative work first, reactive work second. This means blocking off a large chunk of time every day for creative work on your own priorities, with the phone and e-mail off. I used to be a frustrated writer. Making this switch turned me into a productive writer. Now, I start the working day with several hours of writing. I never schedule meetings in the morning, if I can avoid it. So whatever else happens, I always get my most important work done—and looking back, all of my biggest successes have been the result of making this simple change. But it’s better to disappoint a few people over small things, than to surrender your dreams for an empty inbox. Otherwise you’re sacrificing your potential for the illusion of professionalism. Manage Your Day-to-Day: Build Your Routine, Find Your Focus, and Sharpen Your Creative Mind (The 99U Book Series) by Jocelyn K. Glei Georges Simenon was one of the most prolific novelists of the twentieth century, publishing 425 books in his career, including more than 200 works of pulp fiction under 16 different pseudonyms, as well as 220 novels in his own name and three volumes of autobiography. Remarkably, he didn’t write every day.

The Belgian-French novelist worked in intense bursts of literary activity, each lasting two or three weeks, separated by weeks or months of no writing at all. Even during his productive weeks, Simenon didn’t write for very long each day. His typical schedule was to wake at 6:00 A.M., procure coffee, and write from 6:30 to 9:30. Then he would go for a long walk, eat lunch at 12:30, and take a one-hour nap. In the afternoon he spent time with his children and took another walk before dinner, television, and bed at 10:00 P.M. Simenon liked to portray himself as a methodical writing machine—he could compose up to eighty typed pages in a session, making virtually no revisions after the fact—but he did have his share of superstitious behaviors. No one ever saw him working; the “Do Not Disturb” sign he hung on his door was to be taken seriously. He insisted on wearing the same clothes throughout the composition of each novel. He kept tranquilizers in his shirt pocket, in case he needed to ease the anxiety that beset him at the beginning of each new book. And he weighed himself before and after every book, estimating that each one cost him nearly a liter and a half of sweat. Simenon’s astonishing literary productivity was matched, or even surpassed, in one other area of his daily life—his sexual appetite. “Most people work every day and enjoy sex periodically,” Patrick Marnham notes in his biography of the writer. “Simenon had sex every day and every few months indulged in a frenzied orgy of work.” When living in Paris, Simenon frequently slept with four different women in the same day. He estimated that he bedded ten thousand women in his life. (His second wife disagreed, putting the total closer to twelve hundred.) He explained his sexual hunger as the result of “extreme curiosity” about the opposite sex: “Women have always been exceptional people for me whom I have vainly tried to understand. It has been a lifelong, ceaseless quest. And how could I have created dozens, perhaps hundreds, of female characters in my novels if I had not experienced those adventures which lasted for two hours or ten minutes?” Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey It was a brilliant strategy.

Instead of learning how to survive in just one or two ecological niches, we took on the entire globe. Those unable to rapidly solve new problems or learn from mistakes didn’t survive long enough to pass on their genes. The net effect of this evolution was that we didn’t become stronger; we became smarter. We learned to grow our fangs not in the mouth but in the head. This turned out to be a pretty savvy strategy. We went on to conquer the small rift valleys in Eastern Africa. Then we took over the world. Variability Selection Theory predicts some fairly simple things about human learning. It predicts there will be interactions between two powerful features of the brain: a database in which to store a fund of knowledge, and the ability to improvise off of that database. One allows us to know when we’ve made mistakes. The other allows us to learn from them. Both give us the ability to add new information under rapidly changing conditions. Both may be relevant to the way we design classrooms and cubicles. Any learning environment that deals with only the database instincts or only the improvisatory instincts ignores one half of our ability. It is doomed to fail. It makes me think of jazz guitarists: They’re not going to make it if they know a lot about music theory but don’t know how to jam in a live concert. Some schools and workplaces emphasize a stable, rote-learned database. They ignore the improvisatory instincts drilled into us for millions of years. Creativity suffers. Others emphasize creative usage of a database, without installing a fund of knowledge in the first place. They ignore our need to obtain a deep understanding of a subject, which includes memorizing and storing a richly structured database. You get people who are great improvisers but don’t have depth of knowledge. You may know someone like this where you work. They may look like jazz musicians and have the appearance of jamming, but in the end they know nothing. They’re playing intellectual air guitar. Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School by John Medina |

Click to set custom HTML

Categories

All

Disclosure of Material Connection:

Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.” |

Photos from Wesley Oostvogels, Thomas Leuthard, swanksalot, Robert Scoble, Lord Jim, Pink Sherbet Photography, jonrawlinson, MonsterVinVin, M. Pratter, greybeard39, Stepan Mazurov, deanmeyersnet, Patrick Hoesly, Lord Jim, Dcysiv Moment, fdecomite, h.koppdelaney, Abode of Chaos, pasa47, gagilas, BAMCorp, cmjcool, Abode of Chaos, faith goble, nerdcoregirl, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, jmussuto, Easternblot, Jeanne Menjoulet & Cie, aguscr, h.koppdelaney, Saad Faruque, ups2006, Unai_Guerra, erokism, MsSaraKelly, Jem Yoshioka, tony.cairns, david drexler, Reckless Dream Photography, Raffaele1950, kevin dooley, weegeebored, Cast a Line, Zach Dischner, Eddi van W., kmardahl, faungg's photo, Alan Light, acme, Evan Courtney, specialoperations, Mustafa Khayat, darkday., Orin Zebest, Robert S. Donovan, disparkys, kennethkonica, aubergene, Nina Matthews Photography, infomatique, Patrick Hoesly, j0sh (www.pixael.com), SmithGreg, brewbooks, tjsander, The photographer known as Obi, Simone Ramella, striatic, jmussuto, m.a.r.c., jfinnirwin, Nina J. G., pellesten, dreamsjung, misselejane, Design&Joy, eeskaatt, Bravo_Zulu_, No To the Bike Parking Tax, Kecko, quinn.anya, pedrosimoes7, tanakawho, visualpanic, Brooke Hoyer, Barnaby, Fountain_Head, tripandtravelblog, geishaboy500, gordontarpley, Rising Damp, Marc Aubin2009, belboo, torbakhopper, JarleR, aakanayev, santiago nicolau, Official U.S. Navy Imagery, chinnian, GS+, andreasivarsson, paulswansen, victoriapeckham, Thomas8047, timsamoff, ConvenienceStoreGourmet, Jrwooley6, DeeAshley, ethermoon, torbakhopper, Mark Ramsay, dustin larimer, shannonkringen, Stf.O, Todd Huffman, B Rosen, Lord Jim, Jolene4ever, Ben K Adams, Clearly Ambiguous, Daniele Zedda, Ryan Vaarsi, MsSaraKelly, icebrkr, jauhari, ajeofj3, jenny downing, Joi, GollyGforce, Andrew from Sydney, Lord Jim, 'Retard' (says University of Missouri), drukelly, Sullivan Ng, jdxyw, infomatique, AlicePopkorn, RAA408, Abode of Chaos, SaMaNTHa NiGhTsKy, as always..., D@LY3D, Angelo González, the sugary smell of springtime!, Marko Milošević, pedrosimoes7, MartialArtsNomad.com, 401(K) 2013, Sigfrid Lundberg, MoneyBlogNewz, NBphotostream, the stag and doe, Jemima G, bablu121, .reid., jared, EastsideRJ, Alex Alvisi, Marie A.-C., geishaboy500, modomatic, starsnostars., Hardleers, Sarah G..., donielle, Danny PiG, bigcityal, || UggBoy♥UggGirl || PHOTO || WORLD || TRAVEL ||, -KOOPS-, seafaringwoman, kingkongirl, Richard Masoner / Cyclelicious, Hans Gotun, gruntzooki, Duru..., Vectorportal, Peter Hellberg, Alexandre Hamada Possi, Santi Siri, Joshua Rappeneker, a little tune, Patricia Mangual, erokism, woodleywonderworks, Philippe Put, Purple Sherbet Photography, Abode of Chaos, greybeard39, swanksalot, greyloch, Omarukai, Marc_Smith, SLPTWRK, Peter Alfred Hess, illum, MarioMancuso, willc2, _titi, Lightsurgery, Rennett Stowe, feverblue, Esteman., Keith Allison, DCist, h.koppdelaney, Mike Deal aka ZoneDancer, Jos Dielis, The Wandering Angel, Nathaniel KS, MsSaraKelly, Frank Lindecke, Kara Allyson, JeremyGeorge, deoman56, gagilas, Xoan Baltar, Luke Lawreszuk, Eric-P, fdecomite, lorenkerns, masochismtango, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, anarchosyn, -= Bruce Berrien =-, radiant guy, Free Grunge Textures - www.freestock.ca, El Bibliomata, antmoose, Pedro Belleza, Fitsum Belay/iLLIMETER, Nathan O'Nions, denise carbonell, swanksalot, ▓▒░ TORLEY ░▒▓, Marco Gomes, Justin Ornellas, jenni from the block, René Pütsch, eddieq, thombo2, Ben Mortimer Photography, :moolah, ideowl, joaquinuy, wiredforlego, Rafa G. _, derrickcollins, Fishyone1, ben pollard, Admiralspalast Berlin, Georgio, garybirnie.co.uk, fiskfisk, MoreFunkThanYou, xJason.Rogersx, kevin dooley, David Holmes2, Kris Krug, JD Hancock, Images_of_Money, andriux-uk events, Tyfferz, decafinata, jonrawlinson, isado, Lohan Gunaweera, Derek Mindler, Mike "Dakinewavamon" Kline, themostinept, kiwanja, erokism, dktrpepr, Keoni Cabral, denise carbonell, Neal., tonystl, ericmay, Ally Mauro, erokism, Georgie Pauwels, anitakhart, Ivan Zuber, r2hox, Aka Hige, badjonni, striatic, Arry_B, 401(K) 2012, pvera, Lord Jim, Dredrk aka Mr Sky, TerryJohnston, eschipul, wiredforlego, Yuliya Libkina, fabbio, Justin Ruckman, David Boyle, Matthew Oliphant, Keoni Cabral, Thaddeus Maximus, Abode of Chaos, matthias hämmerly, dospaz, LadyDragonflyCC - >;<, CassiusCassini2011, Abode of Chaos, Jorge Luis Perez, infomatique, Mark Gstohl, AliceNWondrlnd, ç嬥x, ssoosay, striatic, NASA Goddard Photo and Video, feverblue, MsSaraKelly, kohlmann.sascha, Vox Efx, country_boy_shane, paularps, Gage Skidmore, HawkinsSteven, Cam Switzer, Arenamontanus, anieto2k, Georgie Pauwels, my camera and me, Lord Jim, nolifebeforecoffee, Joris_Louwes, Kemm 2, VinothChandar, DeeAshley, brewbooks, craigemorsels, Boris Thaser, Poster Boy NYC, ssoosay, guzzphoto, sachac, chefranden, Wanja Photo, Samuel Petersson, onlyart, samsaundersleeds, Ghita Katz Olsen, mcveja, matthewwu88, Victor Bezrukov, JasonLangheine, erokism, vitroid, thethreesisters, charlywkarl, Sharon & Nikki McCutcheon, Ol.v!er [H2vPk], mikecogh, tec_estromberg, noii's, nicholaspaulsmith, Tucker Sherman, Phil Grondin, Cea., Randomthoughtstome, dcobbinau, rafeejewell, pedrosimoes7, lumaxart, marfis75, roland, RLHyde, David Boyle in DC, Sigfrid Lundberg, Thomas Geiregger, Uberto, bgottsab, Conor Lawless, phphoto2010, Steven | Alan, ckaroli, dweekly, AleBonvini, 드림포유, die.tine, MsSaraKelly, equinoxefr, Sarabbit, Abode of Chaos, Galantucci Alessandro, LadyDragonflyCC - >;< - Spring in Michigan!, Alan Gee, Johan Larsson, SoulRider.222, Robert S. Donovan, amslerPIX, cfaobam, Amy L. Riddle, Bladeflyer, Blomstrom, pumpkincat210, Lord Jim, Symic, kevin dooley, pixelthing, Nelson Minar, Fraser Mummery, The Booklight, edenpictures, everyone's idle, betsyweber, h.koppdelaney, ark, Ben Fredericson (xjrlokix), dphiffer, Jeff Kubina, istolethetv, dullhunk, Tambako the Jaguar, fdecomite, The Daily Ornellas, Badruddeen, kevindooley, mnem, Reyes, sadaton, Mary..K, akunamatata, Dennis Vu Photography for Unleashed Media, mitch98000, ganesha.isis, maria j. luque, doneastwest, w00tdew00t, kevindooley, NightFall404, Infrogmation, nandadevieast, darkpatator, Christos Tsoumplekas, sicamp, Hello Turkey Toe, cliff1066™, James Jordan, gailf548, andrew_byrne, infomatique, graphia, -= Bruce Berrien =-, aphrodite-in-nyc, jmussuto, eiko_eiko, Emily Jane Morgan, _Imaji_, kait jarbeau is in love with you, Leeks, h.koppdelaney, paul-simpson.org, Pinti 1, Namlhots, -KOOPS-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed