|

In the future, the great division will be between those who have trained themselves to handle these complexities and those who are overwhelmed by them—those who can acquire skills and discipline their minds and those who are irrevocably distracted by all the media around them and can never focus enough to learn.

Many of our earliest survival skills depended on elaborate hand-eye coordination. To this day, a large portion of our brain is devoted to this relationship. When we work with our hands and build something, we learn how to sequence our actions and how to organize our thoughts. In taking anything apart in order to fix it, we learn problem-solving skills that have wider applications. Even if it is only as a side activity, you should find a way to work with your hands, or to learn more about the inner workings of the machines and pieces of technology around you. Many Masters in history intuited this connection. Thomas Jefferson, who himself was an avid tinkerer and inventor, believed that craftspeople made better citizens because they understood how things functioned and had practical common sense—all of which would serve them well in handling civic needs. Albert Einstein was an avid violinist. He believed that working with his hands in this way and playing music helped his thinking process as well. Mastery by Robert Greene I loved this book.

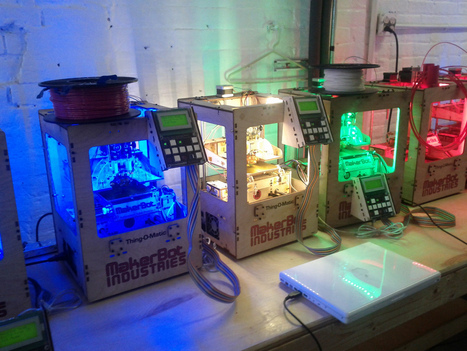

Makers by Chris Anderson is one of my favorite books of 2012. This is the final bit from it, I would recommend you buy a copy and get started creating a business. D So in this appendix, I’ll (Chris Anderson) give a guide to starting with that, using the best recommended tools as of this writing. Getting started with CAD Why? All digital design revolves around software. Whether you’re downloading designs or creating them from scratch, you’ll typically need to use some sort of desktop authoring program to work with the design onscreen. CAD programs range from the free and relatively easy Google SketchUp to complex multithousand-dollar packages such as Solidworks and AutoCAD used by engineers and architects. Recommended 2-D drawing programs • Free option: Inkscape (Windows and Mac) • Paid option: Adobe Illustrator (Windows and Mac) Recommended 3-D drawing programs • Free options: Google SketchUp (Windows and Mac), Autodesk 123D (Windows), TinkerCAD (Web) • Paid option: Solidworks (Windows Recommended 3-D printing solutions • Printers: MakerBot Replicator (best community), Ultimaker (bigger, faster, more expensive) • Services: Shapeways, Ponoko Recommended 3-D scanning solutions • Software: Free Autodesk 123D Catch (iPad; Windows) • Hardware: MakerBot 3-D scanner (requires a webcam and pico projector). Use the free Meshlab software to clean up the image All in all, I recommend that you either do your laser cutting at a local makerspace such as TechShop, or send it to a service bureau that can also source the raw material for you cheaply. Recommended CNC Solutions • Hobby-sized (Dremel tool): MyDIYCNC • Semi-pro: ShopBot Desktop How to start being a Maker in electronics This is the emerging “Internet of Things,” and it starts with simple electronics such as the Arduino physical computing board. All you really need to get started with digital electronics is an Arduino starter kit, a multimeter, and a decent soldering iron. There has never been a better time to find what you need, and companies such as Sparkfun and Adafruit offer not only all the parts you’ll need, but also tutorials, If you want to take it further, you can get a digital logic analyzer, a USB oscilloscope, and a fancy solder rework station. But for starting, the items listed below will take you further than you may have thought possible. Recommended electronics gear • Starter kit: Adafruit budget Arduino kit • Soldering iron: Weller WES51 soldering station • Multimeter: Sparkfun digital multimeter Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by Chris Anderson This second option is a future where the Maker Movement is more about self-sufficiency—making stuff for our own use—than it is about building businesses. It is one that hews even closer to the original ideals of the Homebrew Computer Club and The Whole Earth Catalog.

The idea, then, was not to create big companies, but rather to free ourselves from big companies. This hearkens back to the Israeli kibbutz model of self-sufficiency, which was forged in a period of need and philosophical belief in collective action, or to Gandhi’s model of village industrial independence in India. Of course we’re not all going to grow our own food or easily give up the virtues of a well-stocked shopping mall. But in a future where more things can be fabricated on demand, as opposed to manufactured, shipped, stored, and sold, you can see the opportunity for an industrial economy. Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by Chris Anderson This means that one-person enterprises can get things made in a factory the way only big companies could before. Two trends are driving this. First, there’s the maturation and increasing Web-centrism of business practices in China. Now that the Web generation is entering management, Chinese factories increasingly take orders online, communicate with customers by e-mail, and accept payment by credit card or PayPal, a consumer-friendly alternative to traditional bank transfers, letters of credit, and purchase orders. Second, the current economic crisis has driven companies to seek higher-margin custom orders to mitigate the deflationary spiral of commodity goods.

Institute for the Future’s model for “lightweight innovation.” 1. Network your organizations: “The bike vendors in Chongqing hang out in tea houses and shanzhai vendors in Shenzhen have a vast network centered in the large electronics malls.” 2. Reward solution seekers: “Penny-a-unit profits force the shanzhai collaborations to be totally solutions-driven. They don’t make money if they don’t deliver. ‘Not invented here’ is never a problem.” 3. Err on the side of openness: “The wild west of shanzhai is all about openness. Trade secrets of big companies are flowing freely. Everything is ‘open sourced’ by default. If we take the [intellectual property rights] issue aside, it’s really the ultimate openness we in the open-source world are looking for.” 4. Engage actively: “The shanzhai vendors used to produce knockoffs after original vendors had the products on the market. But in the past year I have seen a lot of them act on the latest Web rumor, especially those related to Apple. It was kind of funny that there were several large-size iPhones (seven-inch and ten-inch) being produced by the shanzhai simply on the rumor that the iPad would look like a large iPhone.” The rise of shanzhai business practices “suggests a new approach to economic recovery as well, one based on small companies well networked with each other,” observes Tom Igoe, a core developer of the open-source Arduino computing platform. “What happens when that approach hits the manufacturing world? We’re about to find out.” Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by Chris Anderson This is just a great book, reading in parts so can stop and think about what I am learning. This is a great example of why social networks have so much power.

D "I set up DIYDrones.com as a social network (on the Ning platform), not as a blog (so 2004!). That distinction—a site created as a community, not a one-man news and information site like a blog—turned out to make all the difference. Like all good social networks, every participant, not just the creator, has access to the full range of authoring tools: along with the usual commenting, they can compose their own blog posts, start discussions, upload videos and pictures, and create profile pages and send messages to one another. Community members can be made moderators, to encourage good behavior and discourage bad. What this meant was that the site wasn’t just about me or my ideas. Instead, it was about anyone who chose to participate. And right from the start, that was almost everyone. The site was soon full of people trading ideas and reports of their own projects and research." Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by Chris Anderson Check out the website mentioned. http://diydrones.com/ As the entrepreneur who founded Babble.com, puts it, “this is the Renaissance of Diletantism.”

The Lean Startup author Eric Reis puts it, Marx got it wrong: “It’s not about ownership of the means of production, anymore. It’s about rentership of the means of production.” Such open supply chains are the mirror of Web publishing and e-commerce a decade ago. The Web, from Amazon to eBay, revealed a Long Tail of demand for niche physical goods; now the democratized tools of production are enabling a Long Tail of supply, too. In a world dominated by one-size-fits-all commodity goods, the way to stand out is to create products that serve individual needs, not general ones. Custom-made bikes fit better. These niche products tend to be driven by people’s wants and needs rather than companies’ wants and needs. Of course people have to create companies to make these goods at scale, but they work hard to retain their roots. Under somewhat different historical conditions, firms using a combination of craft skill and flexible equipment might have played a central role in modern economic life—instead of giving way, in almost all sectors of manufacturing, to corporations based on mass production. Had this line of mechanized craft production prevailed, we might today think of manufacturing firms as linked to particular communities rather than as the independent organizations that, through mass production, seem omnipresent. What does artisanal mean in a digital world? In his 2011 book, The Alphabet and the Algorithm, Mario Carpo, an Italian architectural historian, argues that “variability is the mark of all things handmade.” So far, no surprise for anyone who has bought a tailored suit. But he continues: Now, to a greater extent than was conceivable at the time of manual technologies … the very same process of differentiation can be scripted, programmed, and to some extent designed. Variability can now become part of an automated design and production chain.23 Just consider the Web itself. Each of us sees a different Web. When we visit big Web retailers such as Amazon, the storefront is reorganized just for us, displaying what its algorithms think we’ll most like. Even for pages where the content is the same, the ads are different, inserted by software that evaluates our past behavior and predicts our future actions. We don’t browse the Web, but rather search it, and not only are our search strings different, but different users get different results from the same search strings based on their personal history. Writes Carpo, “This is, at the basis, the golden formula that has made Google a very rich company. Variability, which could be an obstacle in a traditional mechanical environment … has been turned into an asset in the new digital environment—indeed, into one of its most profitable assets.” Variability, which could be an obstacle in a traditional mechanical environment … has been turned into an asset in the new digital environment—indeed, into one of its most profitable assets.” And the more products become information, the more they can be treated as information: collaboratively created by anyone, shared globally online, remixed and reimagined, given away for free, or, if you choose, held secret. In short, the reason atoms are the new bits is that they can increasingly be made to act like bits. But as we’ve learned over the past few decades, digital is different. Sure, digital files can be shared and copied limitlessly at virtually no cost and with no loss of quality. But what’s more important is that they can be modified just as easily. We live in a “remix” culture: everything is inspired by something that came before, and creativity is shown as much in the reinterpretation of existing works as in original ones. That’s always been true (the Greeks argued that there were only seven basic plots, and all stories just changed the details of one or another of them), but it’s never been easier than it is now. Just as Apple encouraged music fans to “Rip. Mix. Burn,” Autodesk now preaches the gospel of “Rip. Mod. Fab” (3-D scan objects, modify them in a CAD program, and print them on a 3-D printer). That ability to easily “remix” digital files is the engine that drives community. What it offers is an invitation to participate. You don’t need to invent something from scratch or have an original idea. Instead, you can participate in a collaborative improvement of existing ideas or designs. The barrier to entry of participation is lower because it’s so easy to modify digital files rather than create them entirely yourself. Think of a digital product design not as a picture of what it should be, but instead as a mathematical equation of how to make it. That is not a metaphor—it’s actually the way CAD programs work. When you draw a 3-D object on the screen, what the computer really does is write a series of geometrical equations that can instruct machines to reproduce the object at any size in any medium, be it pixels on a monitor or plastic in a printer. Increasingly, those equations don’t just describe the shape of a thing, but also its physical properties—what’s flexible and what’s stiff, what conducts electricity and what insulates heat, what’s smooth and what’s rough. So everything is an algorithm now. And just as every Google search uses its algorithms to produce a different result for each person searching, so can algorithms customize products for their consumers. Likewise, the examples where consumers are designing their own products online are rarely mass. Threadless (T-shirts), Lulu (self-published books), CafePress (coffee mugs and other trinkets), and others like them are thriving businesses, but they are platforms for creativity more than great examples of mass customization. They simply give consumers access to small-batch manufacturing on standard platforms: shirts, mugs, and bound paper. Instead, what the new manufacturing model enables is a mass market for niche products. Think ten thousand units, not ten million (mass) or one (mass customization). Products no longer have to sell in big numbers to reach global markets and find their audience. That’s because they don’t do it from the shelves of Wal-Mart. Instead, they use e-commerce, driven by an increasingly discriminating consumer who follows social media and word of mouth to buy specialty products online. In a 2011 speech at Maker Faire, Neil Gershenfeld, the MIT professor whose book Fab: The Coming Revolution on Your Desktop anticipated much of the Maker Movement nearly a decade ago, described his epiphany like this: I realized that the killer app for digital fabrication is personal fabrication. Not to make what you can buy in Wal-Mart, but to make what you can’t buy at Wal-Mart. This is just like the shift from mainframes to personal computers. They weren’t used for the same thing—personal computers are not there for inventory and payroll. Instead personal computers were used for personal things, from e-mail to video games. The same will be true for personal fabrication." Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by Chris Anderson |

Click to set custom HTML

Categories

All

Disclosure of Material Connection:

Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.” |

Photos from Wesley Oostvogels, Thomas Leuthard, swanksalot, Robert Scoble, Lord Jim, Pink Sherbet Photography, jonrawlinson, MonsterVinVin, M. Pratter, greybeard39, Stepan Mazurov, deanmeyersnet, Patrick Hoesly, Lord Jim, Dcysiv Moment, fdecomite, h.koppdelaney, Abode of Chaos, pasa47, gagilas, BAMCorp, cmjcool, Abode of Chaos, faith goble, nerdcoregirl, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, jmussuto, Easternblot, Jeanne Menjoulet & Cie, aguscr, h.koppdelaney, Saad Faruque, ups2006, Unai_Guerra, erokism, MsSaraKelly, Jem Yoshioka, tony.cairns, david drexler, Reckless Dream Photography, Raffaele1950, kevin dooley, weegeebored, Cast a Line, Zach Dischner, Eddi van W., kmardahl, faungg's photo, Alan Light, acme, Evan Courtney, specialoperations, Mustafa Khayat, darkday., Orin Zebest, Robert S. Donovan, disparkys, kennethkonica, aubergene, Nina Matthews Photography, infomatique, Patrick Hoesly, j0sh (www.pixael.com), SmithGreg, brewbooks, tjsander, The photographer known as Obi, Simone Ramella, striatic, jmussuto, m.a.r.c., jfinnirwin, Nina J. G., pellesten, dreamsjung, misselejane, Design&Joy, eeskaatt, Bravo_Zulu_, No To the Bike Parking Tax, Kecko, quinn.anya, pedrosimoes7, tanakawho, visualpanic, Brooke Hoyer, Barnaby, Fountain_Head, tripandtravelblog, geishaboy500, gordontarpley, Rising Damp, Marc Aubin2009, belboo, torbakhopper, JarleR, aakanayev, santiago nicolau, Official U.S. Navy Imagery, chinnian, GS+, andreasivarsson, paulswansen, victoriapeckham, Thomas8047, timsamoff, ConvenienceStoreGourmet, Jrwooley6, DeeAshley, ethermoon, torbakhopper, Mark Ramsay, dustin larimer, shannonkringen, Stf.O, Todd Huffman, B Rosen, Lord Jim, Jolene4ever, Ben K Adams, Clearly Ambiguous, Daniele Zedda, Ryan Vaarsi, MsSaraKelly, icebrkr, jauhari, ajeofj3, jenny downing, Joi, GollyGforce, Andrew from Sydney, Lord Jim, 'Retard' (says University of Missouri), drukelly, Sullivan Ng, jdxyw, infomatique, AlicePopkorn, RAA408, Abode of Chaos, SaMaNTHa NiGhTsKy, as always..., D@LY3D, Angelo González, the sugary smell of springtime!, Marko Milošević, pedrosimoes7, MartialArtsNomad.com, 401(K) 2013, Sigfrid Lundberg, MoneyBlogNewz, NBphotostream, the stag and doe, Jemima G, bablu121, .reid., jared, EastsideRJ, Alex Alvisi, Marie A.-C., geishaboy500, modomatic, starsnostars., Hardleers, Sarah G..., donielle, Danny PiG, bigcityal, || UggBoy♥UggGirl || PHOTO || WORLD || TRAVEL ||, -KOOPS-, seafaringwoman, kingkongirl, Richard Masoner / Cyclelicious, Hans Gotun, gruntzooki, Duru..., Vectorportal, Peter Hellberg, Alexandre Hamada Possi, Santi Siri, Joshua Rappeneker, a little tune, Patricia Mangual, erokism, woodleywonderworks, Philippe Put, Purple Sherbet Photography, Abode of Chaos, greybeard39, swanksalot, greyloch, Omarukai, Marc_Smith, SLPTWRK, Peter Alfred Hess, illum, MarioMancuso, willc2, _titi, Lightsurgery, Rennett Stowe, feverblue, Esteman., Keith Allison, DCist, h.koppdelaney, Mike Deal aka ZoneDancer, Jos Dielis, The Wandering Angel, Nathaniel KS, MsSaraKelly, Frank Lindecke, Kara Allyson, JeremyGeorge, deoman56, gagilas, Xoan Baltar, Luke Lawreszuk, Eric-P, fdecomite, lorenkerns, masochismtango, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, anarchosyn, -= Bruce Berrien =-, radiant guy, Free Grunge Textures - www.freestock.ca, El Bibliomata, antmoose, Pedro Belleza, Fitsum Belay/iLLIMETER, Nathan O'Nions, denise carbonell, swanksalot, ▓▒░ TORLEY ░▒▓, Marco Gomes, Justin Ornellas, jenni from the block, René Pütsch, eddieq, thombo2, Ben Mortimer Photography, :moolah, ideowl, joaquinuy, wiredforlego, Rafa G. _, derrickcollins, Fishyone1, ben pollard, Admiralspalast Berlin, Georgio, garybirnie.co.uk, fiskfisk, MoreFunkThanYou, xJason.Rogersx, kevin dooley, David Holmes2, Kris Krug, JD Hancock, Images_of_Money, andriux-uk events, Tyfferz, decafinata, jonrawlinson, isado, Lohan Gunaweera, Derek Mindler, Mike "Dakinewavamon" Kline, themostinept, kiwanja, erokism, dktrpepr, Keoni Cabral, denise carbonell, Neal., tonystl, ericmay, Ally Mauro, erokism, Georgie Pauwels, anitakhart, Ivan Zuber, r2hox, Aka Hige, badjonni, striatic, Arry_B, 401(K) 2012, pvera, Lord Jim, Dredrk aka Mr Sky, TerryJohnston, eschipul, wiredforlego, Yuliya Libkina, fabbio, Justin Ruckman, David Boyle, Matthew Oliphant, Keoni Cabral, Thaddeus Maximus, Abode of Chaos, matthias hämmerly, dospaz, LadyDragonflyCC - >;<, CassiusCassini2011, Abode of Chaos, Jorge Luis Perez, infomatique, Mark Gstohl, AliceNWondrlnd, ç嬥x, ssoosay, striatic, NASA Goddard Photo and Video, feverblue, MsSaraKelly, kohlmann.sascha, Vox Efx, country_boy_shane, paularps, Gage Skidmore, HawkinsSteven, Cam Switzer, Arenamontanus, anieto2k, Georgie Pauwels, my camera and me, Lord Jim, nolifebeforecoffee, Joris_Louwes, Kemm 2, VinothChandar, DeeAshley, brewbooks, craigemorsels, Boris Thaser, Poster Boy NYC, ssoosay, guzzphoto, sachac, chefranden, Wanja Photo, Samuel Petersson, onlyart, samsaundersleeds, Ghita Katz Olsen, mcveja, matthewwu88, Victor Bezrukov, JasonLangheine, erokism, vitroid, thethreesisters, charlywkarl, Sharon & Nikki McCutcheon, Ol.v!er [H2vPk], mikecogh, tec_estromberg, noii's, nicholaspaulsmith, Tucker Sherman, Phil Grondin, Cea., Randomthoughtstome, dcobbinau, rafeejewell, pedrosimoes7, lumaxart, marfis75, roland, RLHyde, David Boyle in DC, Sigfrid Lundberg, Thomas Geiregger, Uberto, bgottsab, Conor Lawless, phphoto2010, Steven | Alan, ckaroli, dweekly, AleBonvini, 드림포유, die.tine, MsSaraKelly, equinoxefr, Sarabbit, Abode of Chaos, Galantucci Alessandro, LadyDragonflyCC - >;< - Spring in Michigan!, Alan Gee, Johan Larsson, SoulRider.222, Robert S. Donovan, amslerPIX, cfaobam, Amy L. Riddle, Bladeflyer, Blomstrom, pumpkincat210, Lord Jim, Symic, kevin dooley, pixelthing, Nelson Minar, Fraser Mummery, The Booklight, edenpictures, everyone's idle, betsyweber, h.koppdelaney, ark, Ben Fredericson (xjrlokix), dphiffer, Jeff Kubina, istolethetv, dullhunk, Tambako the Jaguar, fdecomite, The Daily Ornellas, Badruddeen, kevindooley, mnem, Reyes, sadaton, Mary..K, akunamatata, Dennis Vu Photography for Unleashed Media, mitch98000, ganesha.isis, maria j. luque, doneastwest, w00tdew00t, kevindooley, NightFall404, Infrogmation, nandadevieast, darkpatator, Christos Tsoumplekas, sicamp, Hello Turkey Toe, cliff1066™, James Jordan, gailf548, andrew_byrne, infomatique, graphia, -= Bruce Berrien =-, aphrodite-in-nyc, jmussuto, eiko_eiko, Emily Jane Morgan, _Imaji_, kait jarbeau is in love with you, Leeks, h.koppdelaney, paul-simpson.org, Pinti 1, Namlhots, -KOOPS-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed