|

Immediately upon moving to Seattle, engineers rather than retail-distribution veterans. He wrote down a list of the ten smartest people he knew and hired them all, including Russell Allgor, a supply-chain engineer at Bayer AG. Wilke had attended Princeton with Allgor and had cribbed from his engineering problem sets. Allgor and his supply-chain algorithms team would become Amazon’s secret weapon, devising mathematical answers to questions such as where and when to stock particular products within Amazon’s distribution network and how to most efficiently combine various items in a customer’s order in a single box.1 Wilke recognized that Amazon had a unique problem in its distribution arm: it was extremely difficult for the company to plan ahead from one shipment to the next. The company didn’t store and ship a predictable number or type of orders. A customer might order one book, a DVD, some tools—perhaps gift-wrapped, perhaps not—and that exact combination might never again be repeated. There were an infinite number of permutations. “We were essentially assembling and fulfilling customer orders. The factory physics were a lot closer to manufacturing and assembly than they were to retail,” Wilke says. So in one of his first moves, Wilke renamed Amazon’s shipping facilities to more accurately represent what was happening there. They were no longer to be called warehouses (the original name) or distribution centers (Jimmy Wright’s name); forever after, they would be known as fulfillment centers, or FCs.

He then applied the process-driven doctrine of Six Sigma that he’d learned at AlliedSignal and mixed it with Toyota’s lean manufacturing philosophy, which requires a company to rationalize every expense in terms of the value it creates for customers and allows workers (now called associates) to pull a red cord and stop all production on the floor if they find a defect (the manufacturing term for the system is andon). In his first two years, Wilke and his team devised dozens of metrics, and he ordered his general managers to track them carefully, including how many shipments each FC received, how many orders were shipped out, and the per-unit cost of packing and shipping each item. He got rid of the older, sometimes frivolous names for mistakes—Amazon’s term to describe the delivery of the wrong product to a customer was switcheroo—and substituted more serious names. And he instilled some basic discipline in the FCs. “When I joined, I didn’t find time clocks,” Wilke says. “People came in when they felt like it in the morning and then went home when the work was done and the last truck was loaded. It wasn’t the kind of rigor I thought would scale.” Wilke promised Bezos that he would reliably generate cost savings each year just by reducing defects and increasing productivity. He told his general managers that on each call, he wanted to know the facts on the ground: how many orders had shipped, how many had not, whether there was a backlog, and, if so, why. As that holiday season ramped up, Wilke also demanded that his managers be prepared to tell him “what was in their yard”—the exact number and contents of the trucks waiting outside the FCs to unload products and ferry orders to the post office or UPS. The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon by Brad Stone Study your reader first—your product second.

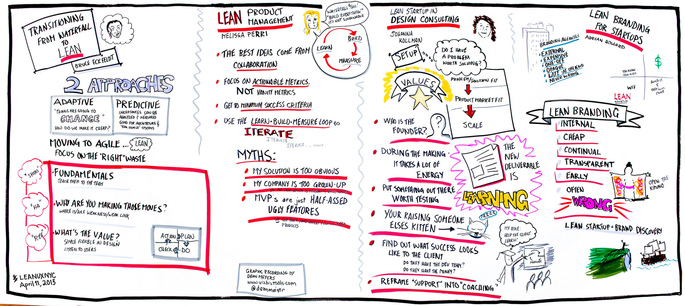

Thousands of articles have been written about the way to use letters to bring you what you want, but the meat of them all can be compressed into two sentences: "What is the bait that will tempt your reader? How can you tie up the thing you have to offer with that bait?" For the ultimate purpose of every business letter simmers down to this: The reader of this letter wants certain things. The desire for them is, consciously or unconsciously, the dominant idea in his mind all the time. You want him to do a certain definite thing for you. How can you tie this up to the thing he wants, in such a way that the doing of it will bring him a step nearer to his goal? In each case, you want him to do something for you. Why should he? Only because of the hope that the doing of it will bring him nearer his heart's desire, or the fear that his failure to do it will remove that heart's desire farther from him. Every mail brings your reader letters urging him to buy this or that, to pay a bill, to get behind some movement or to try a new device. Time was when the mere fact that an envelope looked like a personal letter addressed to him would have intrigued his interest. But that time has long since passed. Letters as letters are no longer objects of intense interest. They are bait neither more nor less—and to tempt him, they must look a bit different from bait he has nibbled at and been fooled by before. They must have something about them that stands out from the mass—that catches his eye and arouses his interest—or away they go into the wastebasket. Your problem, then, is to find a point of contact with his interests, his desires, some feature that will flag his attention and make your letter stand out from all others the moment he reads the first line. But it won't do to yell "Fire!" That will get you attention, yes of a kind but as far as your prospects of doing business are concerned, it will be of the kind a drunken miner got in the days when the West wore guns and used them on the slightest provocation. He stuck his head in the window of a crowded saloon and yelled "Fire!" Study your reader. Find out what interests him. Then study your proposition to see how it can be made to tie in with that interest. The Robert Collier Letter Book by Robert Collier In the Lean Startup model, an experiment is more than just a theoretical inquiry; it is also a first product. If this or any other experiment is successful, it allows the manager to get started with his or her campaign: enlisting early adopters, adding employees to each further experiment or iteration, and eventually starting to build a product. By the time that product is ready to be distributed widely, it will already have established customers. It will have solved real problems and offer detailed specifications for what needs to be built. Unlike a traditional strategic planning or market research process, this specification will be rooted in feedback on what is working today rather than in anticipation of what might work tomorrow.

Questions to ask; 1. Do consumers recognize that they have the problem you are trying to solve? 2. If there was a solution, would they buy it? 3. Would they buy it from us? 4. Can we build a solution for that problem?” “Success is not delivering a feature; success is learning how to solve the customer’s problem.” The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses by Eric Ries I believe that entrepreneurship requires a managerial discipline to harness the entrepreneurial opportunity we have been given.

There are more entrepreneurs operating today than at any previous time in history. This has been made possible by dramatic changes in the global economy. To cite but one example, one often hears commentators lament the loss of manufacturing jobs in the United States over the previous two decades, but one rarely hears about a corresponding loss of manufacturing capability. That’s because total manufacturing output in the United States is increasing (by 15 percent in the last decade) even as jobs continue to be lost (see the charts below). In effect, the huge productivity increases made possible by modern management and technology have created more productive capacity than firms know what to do with. We are living through an unprecedented worldwide entrepreneurial renaissance, but this opportunity is laced with peril. Because we lack a coherent management paradigm for new innovative ventures, we’re throwing our excess capacity around with wild abandon. Despite this lack of rigor, we are finding some ways to make money, but for every success there are far too many failures: products pulled from shelves mere weeks after being launched, high-profile startups lauded in the press and forgotten a few months later, and new products that wind up being used by nobody. What makes these failures particularly painful is not just the economic damage done to individual employees, companies, and investors; they are also a colossal waste of our civilization’s most precious resource: the time, passion, and skill of its people. The Lean Startup movement is dedicated to preventing these failures. Lean thinking is radically altering the way supply chains and production systems are run. Among its tenets are drawing on the knowledge and creativity of individual workers, the shrinking of batch sizes, just-in-time production and inventory control, and an acceleration of cycle times. It taught the world the difference between value-creating activities and waste and showed how to build quality into products from the inside out. Progress in manufacturing is measured by the production of high-quality physical goods....the Lean Startup uses a different unit of progress, called validated learning. With scientific learning as our yardstick, we can discover and eliminate the sources of waste that are plaguing entrepreneurship. The Lean Startup: How Today's Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses by Eric Ries In the future, the great division will be between those who have trained themselves to handle these complexities and those who are overwhelmed by them—those who can acquire skills and discipline their minds and those who are irrevocably distracted by all the media around them and can never focus enough to learn.

Many of our earliest survival skills depended on elaborate hand-eye coordination. To this day, a large portion of our brain is devoted to this relationship. When we work with our hands and build something, we learn how to sequence our actions and how to organize our thoughts. In taking anything apart in order to fix it, we learn problem-solving skills that have wider applications. Even if it is only as a side activity, you should find a way to work with your hands, or to learn more about the inner workings of the machines and pieces of technology around you. Many Masters in history intuited this connection. Thomas Jefferson, who himself was an avid tinkerer and inventor, believed that craftspeople made better citizens because they understood how things functioned and had practical common sense—all of which would serve them well in handling civic needs. Albert Einstein was an avid violinist. He believed that working with his hands in this way and playing music helped his thinking process as well. Mastery by Robert Greene Process is King

Documenting repeatable processes for anything you will do more than once is essential to your sanity. It’s true; you can fly by the seat of your pants and get by, but it makes you a hostage to your work. If you’ve ever been a manager you probably like process and understand its benefits. If you’re a developer you probably dislike process or see it as a necessary evil. Startups, being lean and mean, seem like the perfect place to eliminate documents, have no systems, and no processes…but that’s far from the truth. Without process it’s impossible to delegate, difficult to bring on a business partner, and easy to make mistakes. With processes in place it’s much easier to sell your product if/when you want to make an exit. The fact is, creating processes will bring you freedom through the ability to easily automate and outsource tasks. Start Small, Stay Small: A Developer's Guide to Launching a Startup by Rob Walling There are literally thousands of different ways to get recognition for your expertise.

Try moonlighting. See if you have the time to take on freelance projects that will bring you in touch with a whole new group of people. Or, within your own company, take on an extra project that might showcase your new skills. Teach a class or give a workshop at your own company. Sign up to be on panel discussions at a conference. Most important, remember that your circle of friends, colleagues, clients, and customers is the most powerful vehicle you’ve got to get the word out about what you do. What they say about you will ultimately determine the value of your brand. Never Eat Alone: And Other Secrets to Success, One Relationship at a Time by Keith Ferrazzi, Tahl Raz I loved this book.

Makers by Chris Anderson is one of my favorite books of 2012. This is the final bit from it, I would recommend you buy a copy and get started creating a business. D So in this appendix, I’ll (Chris Anderson) give a guide to starting with that, using the best recommended tools as of this writing. Getting started with CAD Why? All digital design revolves around software. Whether you’re downloading designs or creating them from scratch, you’ll typically need to use some sort of desktop authoring program to work with the design onscreen. CAD programs range from the free and relatively easy Google SketchUp to complex multithousand-dollar packages such as Solidworks and AutoCAD used by engineers and architects. Recommended 2-D drawing programs • Free option: Inkscape (Windows and Mac) • Paid option: Adobe Illustrator (Windows and Mac) Recommended 3-D drawing programs • Free options: Google SketchUp (Windows and Mac), Autodesk 123D (Windows), TinkerCAD (Web) • Paid option: Solidworks (Windows Recommended 3-D printing solutions • Printers: MakerBot Replicator (best community), Ultimaker (bigger, faster, more expensive) • Services: Shapeways, Ponoko Recommended 3-D scanning solutions • Software: Free Autodesk 123D Catch (iPad; Windows) • Hardware: MakerBot 3-D scanner (requires a webcam and pico projector). Use the free Meshlab software to clean up the image All in all, I recommend that you either do your laser cutting at a local makerspace such as TechShop, or send it to a service bureau that can also source the raw material for you cheaply. Recommended CNC Solutions • Hobby-sized (Dremel tool): MyDIYCNC • Semi-pro: ShopBot Desktop How to start being a Maker in electronics This is the emerging “Internet of Things,” and it starts with simple electronics such as the Arduino physical computing board. All you really need to get started with digital electronics is an Arduino starter kit, a multimeter, and a decent soldering iron. There has never been a better time to find what you need, and companies such as Sparkfun and Adafruit offer not only all the parts you’ll need, but also tutorials, If you want to take it further, you can get a digital logic analyzer, a USB oscilloscope, and a fancy solder rework station. But for starting, the items listed below will take you further than you may have thought possible. Recommended electronics gear • Starter kit: Adafruit budget Arduino kit • Soldering iron: Weller WES51 soldering station • Multimeter: Sparkfun digital multimeter Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by Chris Anderson This second option is a future where the Maker Movement is more about self-sufficiency—making stuff for our own use—than it is about building businesses. It is one that hews even closer to the original ideals of the Homebrew Computer Club and The Whole Earth Catalog.

The idea, then, was not to create big companies, but rather to free ourselves from big companies. This hearkens back to the Israeli kibbutz model of self-sufficiency, which was forged in a period of need and philosophical belief in collective action, or to Gandhi’s model of village industrial independence in India. Of course we’re not all going to grow our own food or easily give up the virtues of a well-stocked shopping mall. But in a future where more things can be fabricated on demand, as opposed to manufactured, shipped, stored, and sold, you can see the opportunity for an industrial economy. Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by Chris Anderson Remember that line from Cory Doctorow’s book:

The days of companies with names like “General Electric” and “General Mills” and “General Motors” are over. The money on the table is like krill: a billion little entrepreneurial opportunities that can be discovered and exploited by smart, creative people. Makers: The New Industrial Revolution by Chris Anderson |

Click to set custom HTML

Categories

All

Disclosure of Material Connection:

Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.” |

Photos from Wesley Oostvogels, Thomas Leuthard, swanksalot, Robert Scoble, Lord Jim, Pink Sherbet Photography, jonrawlinson, MonsterVinVin, M. Pratter, greybeard39, Stepan Mazurov, deanmeyersnet, Patrick Hoesly, Lord Jim, Dcysiv Moment, fdecomite, h.koppdelaney, Abode of Chaos, pasa47, gagilas, BAMCorp, cmjcool, Abode of Chaos, faith goble, nerdcoregirl, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, jmussuto, Easternblot, Jeanne Menjoulet & Cie, aguscr, h.koppdelaney, Saad Faruque, ups2006, Unai_Guerra, erokism, MsSaraKelly, Jem Yoshioka, tony.cairns, david drexler, Reckless Dream Photography, Raffaele1950, kevin dooley, weegeebored, Cast a Line, Zach Dischner, Eddi van W., kmardahl, faungg's photo, Alan Light, acme, Evan Courtney, specialoperations, Mustafa Khayat, darkday., Orin Zebest, Robert S. Donovan, disparkys, kennethkonica, aubergene, Nina Matthews Photography, infomatique, Patrick Hoesly, j0sh (www.pixael.com), SmithGreg, brewbooks, tjsander, The photographer known as Obi, Simone Ramella, striatic, jmussuto, m.a.r.c., jfinnirwin, Nina J. G., pellesten, dreamsjung, misselejane, Design&Joy, eeskaatt, Bravo_Zulu_, No To the Bike Parking Tax, Kecko, quinn.anya, pedrosimoes7, tanakawho, visualpanic, Brooke Hoyer, Barnaby, Fountain_Head, tripandtravelblog, geishaboy500, gordontarpley, Rising Damp, Marc Aubin2009, belboo, torbakhopper, JarleR, aakanayev, santiago nicolau, Official U.S. Navy Imagery, chinnian, GS+, andreasivarsson, paulswansen, victoriapeckham, Thomas8047, timsamoff, ConvenienceStoreGourmet, Jrwooley6, DeeAshley, ethermoon, torbakhopper, Mark Ramsay, dustin larimer, shannonkringen, Stf.O, Todd Huffman, B Rosen, Lord Jim, Jolene4ever, Ben K Adams, Clearly Ambiguous, Daniele Zedda, Ryan Vaarsi, MsSaraKelly, icebrkr, jauhari, ajeofj3, jenny downing, Joi, GollyGforce, Andrew from Sydney, Lord Jim, 'Retard' (says University of Missouri), drukelly, Sullivan Ng, jdxyw, infomatique, AlicePopkorn, RAA408, Abode of Chaos, SaMaNTHa NiGhTsKy, as always..., D@LY3D, Angelo González, the sugary smell of springtime!, Marko Milošević, pedrosimoes7, MartialArtsNomad.com, 401(K) 2013, Sigfrid Lundberg, MoneyBlogNewz, NBphotostream, the stag and doe, Jemima G, bablu121, .reid., jared, EastsideRJ, Alex Alvisi, Marie A.-C., geishaboy500, modomatic, starsnostars., Hardleers, Sarah G..., donielle, Danny PiG, bigcityal, || UggBoy♥UggGirl || PHOTO || WORLD || TRAVEL ||, -KOOPS-, seafaringwoman, kingkongirl, Richard Masoner / Cyclelicious, Hans Gotun, gruntzooki, Duru..., Vectorportal, Peter Hellberg, Alexandre Hamada Possi, Santi Siri, Joshua Rappeneker, a little tune, Patricia Mangual, erokism, woodleywonderworks, Philippe Put, Purple Sherbet Photography, Abode of Chaos, greybeard39, swanksalot, greyloch, Omarukai, Marc_Smith, SLPTWRK, Peter Alfred Hess, illum, MarioMancuso, willc2, _titi, Lightsurgery, Rennett Stowe, feverblue, Esteman., Keith Allison, DCist, h.koppdelaney, Mike Deal aka ZoneDancer, Jos Dielis, The Wandering Angel, Nathaniel KS, MsSaraKelly, Frank Lindecke, Kara Allyson, JeremyGeorge, deoman56, gagilas, Xoan Baltar, Luke Lawreszuk, Eric-P, fdecomite, lorenkerns, masochismtango, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, anarchosyn, -= Bruce Berrien =-, radiant guy, Free Grunge Textures - www.freestock.ca, El Bibliomata, antmoose, Pedro Belleza, Fitsum Belay/iLLIMETER, Nathan O'Nions, denise carbonell, swanksalot, ▓▒░ TORLEY ░▒▓, Marco Gomes, Justin Ornellas, jenni from the block, René Pütsch, eddieq, thombo2, Ben Mortimer Photography, :moolah, ideowl, joaquinuy, wiredforlego, Rafa G. _, derrickcollins, Fishyone1, ben pollard, Admiralspalast Berlin, Georgio, garybirnie.co.uk, fiskfisk, MoreFunkThanYou, xJason.Rogersx, kevin dooley, David Holmes2, Kris Krug, JD Hancock, Images_of_Money, andriux-uk events, Tyfferz, decafinata, jonrawlinson, isado, Lohan Gunaweera, Derek Mindler, Mike "Dakinewavamon" Kline, themostinept, kiwanja, erokism, dktrpepr, Keoni Cabral, denise carbonell, Neal., tonystl, ericmay, Ally Mauro, erokism, Georgie Pauwels, anitakhart, Ivan Zuber, r2hox, Aka Hige, badjonni, striatic, Arry_B, 401(K) 2012, pvera, Lord Jim, Dredrk aka Mr Sky, TerryJohnston, eschipul, wiredforlego, Yuliya Libkina, fabbio, Justin Ruckman, David Boyle, Matthew Oliphant, Keoni Cabral, Thaddeus Maximus, Abode of Chaos, matthias hämmerly, dospaz, LadyDragonflyCC - >;<, CassiusCassini2011, Abode of Chaos, Jorge Luis Perez, infomatique, Mark Gstohl, AliceNWondrlnd, ç嬥x, ssoosay, striatic, NASA Goddard Photo and Video, feverblue, MsSaraKelly, kohlmann.sascha, Vox Efx, country_boy_shane, paularps, Gage Skidmore, HawkinsSteven, Cam Switzer, Arenamontanus, anieto2k, Georgie Pauwels, my camera and me, Lord Jim, nolifebeforecoffee, Joris_Louwes, Kemm 2, VinothChandar, DeeAshley, brewbooks, craigemorsels, Boris Thaser, Poster Boy NYC, ssoosay, guzzphoto, sachac, chefranden, Wanja Photo, Samuel Petersson, onlyart, samsaundersleeds, Ghita Katz Olsen, mcveja, matthewwu88, Victor Bezrukov, JasonLangheine, erokism, vitroid, thethreesisters, charlywkarl, Sharon & Nikki McCutcheon, Ol.v!er [H2vPk], mikecogh, tec_estromberg, noii's, nicholaspaulsmith, Tucker Sherman, Phil Grondin, Cea., Randomthoughtstome, dcobbinau, rafeejewell, pedrosimoes7, lumaxart, marfis75, roland, RLHyde, David Boyle in DC, Sigfrid Lundberg, Thomas Geiregger, Uberto, bgottsab, Conor Lawless, phphoto2010, Steven | Alan, ckaroli, dweekly, AleBonvini, 드림포유, die.tine, MsSaraKelly, equinoxefr, Sarabbit, Abode of Chaos, Galantucci Alessandro, LadyDragonflyCC - >;< - Spring in Michigan!, Alan Gee, Johan Larsson, SoulRider.222, Robert S. Donovan, amslerPIX, cfaobam, Amy L. Riddle, Bladeflyer, Blomstrom, pumpkincat210, Lord Jim, Symic, kevin dooley, pixelthing, Nelson Minar, Fraser Mummery, The Booklight, edenpictures, everyone's idle, betsyweber, h.koppdelaney, ark, Ben Fredericson (xjrlokix), dphiffer, Jeff Kubina, istolethetv, dullhunk, Tambako the Jaguar, fdecomite, The Daily Ornellas, Badruddeen, kevindooley, mnem, Reyes, sadaton, Mary..K, akunamatata, Dennis Vu Photography for Unleashed Media, mitch98000, ganesha.isis, maria j. luque, doneastwest, w00tdew00t, kevindooley, NightFall404, Infrogmation, nandadevieast, darkpatator, Christos Tsoumplekas, sicamp, Hello Turkey Toe, cliff1066™, James Jordan, gailf548, andrew_byrne, infomatique, graphia, -= Bruce Berrien =-, aphrodite-in-nyc, jmussuto, eiko_eiko, Emily Jane Morgan, _Imaji_, kait jarbeau is in love with you, Leeks, h.koppdelaney, paul-simpson.org, Pinti 1, Namlhots, -KOOPS-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed