|

It was a brilliant strategy.

Instead of learning how to survive in just one or two ecological niches, we took on the entire globe. Those unable to rapidly solve new problems or learn from mistakes didn’t survive long enough to pass on their genes. The net effect of this evolution was that we didn’t become stronger; we became smarter. We learned to grow our fangs not in the mouth but in the head. This turned out to be a pretty savvy strategy. We went on to conquer the small rift valleys in Eastern Africa. Then we took over the world. Variability Selection Theory predicts some fairly simple things about human learning. It predicts there will be interactions between two powerful features of the brain: a database in which to store a fund of knowledge, and the ability to improvise off of that database. One allows us to know when we’ve made mistakes. The other allows us to learn from them. Both give us the ability to add new information under rapidly changing conditions. Both may be relevant to the way we design classrooms and cubicles. Any learning environment that deals with only the database instincts or only the improvisatory instincts ignores one half of our ability. It is doomed to fail. It makes me think of jazz guitarists: They’re not going to make it if they know a lot about music theory but don’t know how to jam in a live concert. Some schools and workplaces emphasize a stable, rote-learned database. They ignore the improvisatory instincts drilled into us for millions of years. Creativity suffers. Others emphasize creative usage of a database, without installing a fund of knowledge in the first place. They ignore our need to obtain a deep understanding of a subject, which includes memorizing and storing a richly structured database. You get people who are great improvisers but don’t have depth of knowledge. You may know someone like this where you work. They may look like jazz musicians and have the appearance of jamming, but in the end they know nothing. They’re playing intellectual air guitar. Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School by John Medina . . . just as a matter of interest, tell me something: how long do you sleep each night?

The proverbial eight hours. Ask anyone and they say automatically ‘eight hours’. As a matter of fact you sleep about ten and a half hours, like the majority of people. I’ve timed you on a number of occasions. I myself sleep eleven. Yet thirty years ago people did indeed sleep eight hours, and a century before that they slept six or seven. In Vasari’s Lives one reads of Michelangelo sleeping for only four or five hours, painting all day at the age of eighty and then working through the night over his anatomy table with a candle strapped to his forehead. Now he’s regarded as a prodigy, but it was unremarkable then. How do you think the ancients, from Plato to Shakespeare, Aristotle to Aquinas, were able to cram so much work into their lives? Simply because they had an extra six or seven hours every day. The Complete Stories of J. G. Ballard by J. G. Ballard To find one’s place in the world, to learn how to live and act, we must first obtain knowledge of the world in which we find ourselves. This is the first task of a philosophical ‘theory’

If we want to form a simple idea of what was meant by kosmos, we must imagine the whole of the universe as if it were both ordered and animate. For the Stoics, the structure of the world – the cosmic order – is not merely magnificent, it is also comparable to a living being. The material world, the entire universe, fundamentally resembles a gigantic animal, of which each element – each organ – is conceived and adapted to the harmonious functioning of the whole. Each part, each member of this immense body, is perfectly in place and functions impeccably (although disasters do occur, they do not last for long, and order is soon restored) in the most literal sense: without fault, and in harmony with the other parts. And it is this that theoria helps us to unravel and understand. What Marcus Aurelius suggests amounts to the idea that nature – when it functions normally and aside from the occasional accidents and catastrophes that occur – renders justice finally to each of us. It supplies to each of us our essential needs as individuals: a body which enables us to move about the world, an intelligence which permits us to adapt to the world, and natural resources which enable us to survive in the world. So that, in this great cosmic sharing out of goods, each receives his due. A Brief History of Thought: A Philosophical Guide to Living by Luc Ferry The best mentors are often those who have wide knowledge and experience, and are not overly specialized in their field—they can train you to think on a higher level, and to make connections between different forms of knowledge.

The paradigm for this is the Aristotle–Alexander the Great relationship. Philip II, Alexander’s father and king of Macedonia, chose Aristotle to mentor his thirteen-year-old son because the philosopher had learned and mastered so many different fields. He could thus impart to Alexander an overall love of learning, and teach him how to think and reason in any kind of situation—the greatest skill of all. This ended up working to perfection. Alexander was able to effectively apply the reasoning skills he had gained from Aristotle to politics and warfare. To the end of his life he maintained an intense curiosity for any field of knowledge, and would always gather about him experts he could learn from. Aristotle had imparted a form of wisdom that played a key role in Alexander’s success. Mastery by Robert Greene The model goes like this:

You want to learn as many skills as possible, following the direction that circumstances lead you to, but only if they are related to your deepest interests. Like a hacker, you value the process of self-discovery and making things that are of the highest quality. You avoid the trap of following one set career path. You are not sure where this will all lead, but you are taking full advantage of the openness of information, all of the knowledge about skills now at our disposal. You see what kind of work suits you and what you want to avoid at all cost. You move by trial and error. This is how you pass your twenties. You are the programmer of this wide-ranging apprenticeship, within the loose constraints of your personal interests. You are not wandering about because you are afraid of commitment, but because you are expanding your skill base and your possibilities. At a certain point, when you are ready to settle on something, ideas and opportunities will inevitably present themselves to you. When that happens, all of the skills you have accumulated will prove invaluable. You will be the Master at combining them in ways that are unique and suited to your individuality. You may settle on this one place or idea for several years, accumulating in the process even more skills, then move in a slightly different direction when the time is appropriate. In this new age, those who follow a rigid, singular path in their youth often find themselves in a career dead end in their forties, or overwhelmed with boredom. The wide-ranging apprenticeship of your twenties will yield the opposite—expanding possibilities as you get older. Mastery by Robert Greene I like the idea that all ideas need to have actions and facts tied to them. Without that, they are just wishes. No idea, action, business concept should ignore scientific knowledge.

D ‘Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here,’ said Plato to his students, referring to his school, the Academy; and thereafter no philosophy has ever seriously proposed to ignore scientific knowledge. If philosophy, like religion, has its deepest roots in human ‘finiteness’ – the fact that for us mortals time is limited, and that we are the only beings in this world to be fully aware of this fact – it goes without saying that the question of what to do with our time cannot be avoided. As distinct from trees, oysters and rabbits, we think constantly about our relationship to time: about how we are going to spend the next hour or this evening, or the coming year. And sooner or later we are confronted – sometimes due to a sudden event that breaks our daily routine – with the question of what we are doing, what we should be doing, and what we must be doing with our lives – our time – as a whole. This thought process has three distinct stages: a theoretical stage, a moral or ethical stage, and a crowning conclusion as to salvation or wisdom and this leads to two fundamental questions... These two questions – the nature of the world, and the instruments for understanding it at our disposal as humans –"these" constitute the essentials of the theoretical aspect of philosophy. To be a sage, by definition, is neither to aspire to wisdom or seek the condition of being a sage, but simply to live wisely, contentedly and as freely as possible, having finally overcome the fears sparked in us by our own finiteness. To find one’s place in the world, to learn how to live and act, we must first obtain knowledge of the world in which we find ourselves. This is the first task of a philosophical ‘theory’ A Brief History of Thought: A Philosophical Guide to Living by Luc Ferry I am convinced that everyone should study just a little philosophy.

The philosopher is above all one who believes that by understanding the world, by understanding ourselves and others as far our intelligence permits, we shall succeed in overcoming fear, through clear-sightedness rather than blind faith. Greek philosophers looked upon the past and the future as the primary evils weighing upon human life, and as the source of all the anxieties which blight the present. The present moment is the only dimension of existence worth inhabiting, because it is the only one available to us. The past is no longer and the future has yet to come, they liked to remind us; yet we live virtually all of our lives somewhere between memories and aspirations, nostalgia and expectation. We imagine we would be much happier with new shoes, a faster computer, a bigger house, more exotic holidays, different friends … But by regretting the past or guessing the future, we end up missing the only life worth living: the one which proceeds from the here and now and deserves to be savoured. A Brief History of Thought: A Philosophical Guide to Living by Luc Ferry But by regretting the past or guessing the future, we end up missing the only life worth living1/22/2013

Greek philosophers looked upon the past and the future as the primary evils weighing upon human life, and as the source of all the anxieties which blight the present. The present moment is the only dimension of existence worth inhabiting, because it is the only one available to us. The past is no longer and the future has yet to come, they liked to remind us; yet we live virtually all of our lives somewhere between memories and aspirations, nostalgia and expectation. We imagine we would be much happier with new shoes, a faster computer, a bigger house, more exotic holidays, different friends … But by regretting the past or guessing the future, we end up missing the only life worth living: the one which proceeds from the here and now and deserves to be savoured.

A Brief History of Thought: A Philosophical Guide to Living by Luc Ferry In moving toward mastery, you are bringing your mind closer to reality and to life itself.

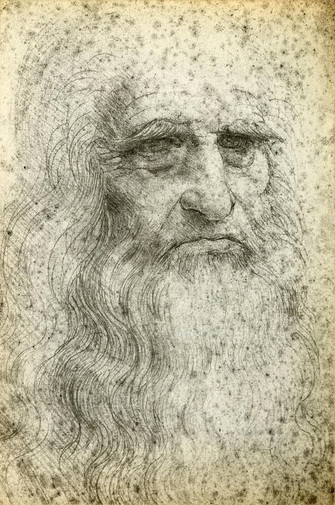

Anything that is alive is in a continual state of change and movement. The moment that you rest, thinking that you have attained the level you desire, a part of your mind enters a phase of decay. You lose your hard-earned creativity and others begin to sense it. This is a power and intelligence that must be continually renewed or it will die. .....Verrocchio instructed his apprentices in all of the sciences that were necessary to produce the work of his studio—engineering, mechanics, chemistry, and metallurgy. Leonardo was eager to learn all of these skills, but soon he discovered in himself something else: he could not simply do an assignment; he needed to make it something of his own, to invent rather than imitate the Master. For Napoleon Bonaparte it was his “star” that he always felt in ascendance when he made the right move. For Socrates, it was his daemon, a voice that he heard, perhaps from the gods, which inevitably spoke to him in the negative—telling him what to avoid. For Goethe, he also called it a daemon—a kind of spirit that dwelled within him and compelled him to fulfill his destiny. In more modern times, Albert Einstein talked of a kind of inner voice that shaped the direction of his speculations. All of these are variations on what Leonardo da Vinci experienced with his own sense of fate Mastery by Robert Greene "That's been one of my mantras -- focus and simplicity. Simple can be harder than complex: You have to work hard to get your thinking clean to make it simple. But it's worth it in the end because once you get there, you can move mountains."

"Picasso had a saying: 'Good artists copy, great artists steal.' We have always been shameless about stealing great ideas...I think part of what made the Macintosh great was that the people working on it were musicians, poets, artists, zoologists and historians who also happened to be the best computer scientists in the world." Steve Jobs-- 1994 |

Click to set custom HTML

Categories

All

Disclosure of Material Connection:

Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.” |

Photos from Wesley Oostvogels, Thomas Leuthard, swanksalot, Robert Scoble, Lord Jim, Pink Sherbet Photography, jonrawlinson, MonsterVinVin, M. Pratter, greybeard39, Stepan Mazurov, deanmeyersnet, Patrick Hoesly, Lord Jim, Dcysiv Moment, fdecomite, h.koppdelaney, Abode of Chaos, pasa47, gagilas, BAMCorp, cmjcool, Abode of Chaos, faith goble, nerdcoregirl, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, jmussuto, Easternblot, Jeanne Menjoulet & Cie, aguscr, h.koppdelaney, Saad Faruque, ups2006, Unai_Guerra, erokism, MsSaraKelly, Jem Yoshioka, tony.cairns, david drexler, Reckless Dream Photography, Raffaele1950, kevin dooley, weegeebored, Cast a Line, Zach Dischner, Eddi van W., kmardahl, faungg's photo, Alan Light, acme, Evan Courtney, specialoperations, Mustafa Khayat, darkday., Orin Zebest, Robert S. Donovan, disparkys, kennethkonica, aubergene, Nina Matthews Photography, infomatique, Patrick Hoesly, j0sh (www.pixael.com), SmithGreg, brewbooks, tjsander, The photographer known as Obi, Simone Ramella, striatic, jmussuto, m.a.r.c., jfinnirwin, Nina J. G., pellesten, dreamsjung, misselejane, Design&Joy, eeskaatt, Bravo_Zulu_, No To the Bike Parking Tax, Kecko, quinn.anya, pedrosimoes7, tanakawho, visualpanic, Brooke Hoyer, Barnaby, Fountain_Head, tripandtravelblog, geishaboy500, gordontarpley, Rising Damp, Marc Aubin2009, belboo, torbakhopper, JarleR, aakanayev, santiago nicolau, Official U.S. Navy Imagery, chinnian, GS+, andreasivarsson, paulswansen, victoriapeckham, Thomas8047, timsamoff, ConvenienceStoreGourmet, Jrwooley6, DeeAshley, ethermoon, torbakhopper, Mark Ramsay, dustin larimer, shannonkringen, Stf.O, Todd Huffman, B Rosen, Lord Jim, Jolene4ever, Ben K Adams, Clearly Ambiguous, Daniele Zedda, Ryan Vaarsi, MsSaraKelly, icebrkr, jauhari, ajeofj3, jenny downing, Joi, GollyGforce, Andrew from Sydney, Lord Jim, 'Retard' (says University of Missouri), drukelly, Sullivan Ng, jdxyw, infomatique, AlicePopkorn, RAA408, Abode of Chaos, SaMaNTHa NiGhTsKy, as always..., D@LY3D, Angelo González, the sugary smell of springtime!, Marko Milošević, pedrosimoes7, MartialArtsNomad.com, 401(K) 2013, Sigfrid Lundberg, MoneyBlogNewz, NBphotostream, the stag and doe, Jemima G, bablu121, .reid., jared, EastsideRJ, Alex Alvisi, Marie A.-C., geishaboy500, modomatic, starsnostars., Hardleers, Sarah G..., donielle, Danny PiG, bigcityal, || UggBoy♥UggGirl || PHOTO || WORLD || TRAVEL ||, -KOOPS-, seafaringwoman, kingkongirl, Richard Masoner / Cyclelicious, Hans Gotun, gruntzooki, Duru..., Vectorportal, Peter Hellberg, Alexandre Hamada Possi, Santi Siri, Joshua Rappeneker, a little tune, Patricia Mangual, erokism, woodleywonderworks, Philippe Put, Purple Sherbet Photography, Abode of Chaos, greybeard39, swanksalot, greyloch, Omarukai, Marc_Smith, SLPTWRK, Peter Alfred Hess, illum, MarioMancuso, willc2, _titi, Lightsurgery, Rennett Stowe, feverblue, Esteman., Keith Allison, DCist, h.koppdelaney, Mike Deal aka ZoneDancer, Jos Dielis, The Wandering Angel, Nathaniel KS, MsSaraKelly, Frank Lindecke, Kara Allyson, JeremyGeorge, deoman56, gagilas, Xoan Baltar, Luke Lawreszuk, Eric-P, fdecomite, lorenkerns, masochismtango, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, anarchosyn, -= Bruce Berrien =-, radiant guy, Free Grunge Textures - www.freestock.ca, El Bibliomata, antmoose, Pedro Belleza, Fitsum Belay/iLLIMETER, Nathan O'Nions, denise carbonell, swanksalot, ▓▒░ TORLEY ░▒▓, Marco Gomes, Justin Ornellas, jenni from the block, René Pütsch, eddieq, thombo2, Ben Mortimer Photography, :moolah, ideowl, joaquinuy, wiredforlego, Rafa G. _, derrickcollins, Fishyone1, ben pollard, Admiralspalast Berlin, Georgio, garybirnie.co.uk, fiskfisk, MoreFunkThanYou, xJason.Rogersx, kevin dooley, David Holmes2, Kris Krug, JD Hancock, Images_of_Money, andriux-uk events, Tyfferz, decafinata, jonrawlinson, isado, Lohan Gunaweera, Derek Mindler, Mike "Dakinewavamon" Kline, themostinept, kiwanja, erokism, dktrpepr, Keoni Cabral, denise carbonell, Neal., tonystl, ericmay, Ally Mauro, erokism, Georgie Pauwels, anitakhart, Ivan Zuber, r2hox, Aka Hige, badjonni, striatic, Arry_B, 401(K) 2012, pvera, Lord Jim, Dredrk aka Mr Sky, TerryJohnston, eschipul, wiredforlego, Yuliya Libkina, fabbio, Justin Ruckman, David Boyle, Matthew Oliphant, Keoni Cabral, Thaddeus Maximus, Abode of Chaos, matthias hämmerly, dospaz, LadyDragonflyCC - >;<, CassiusCassini2011, Abode of Chaos, Jorge Luis Perez, infomatique, Mark Gstohl, AliceNWondrlnd, ç嬥x, ssoosay, striatic, NASA Goddard Photo and Video, feverblue, MsSaraKelly, kohlmann.sascha, Vox Efx, country_boy_shane, paularps, Gage Skidmore, HawkinsSteven, Cam Switzer, Arenamontanus, anieto2k, Georgie Pauwels, my camera and me, Lord Jim, nolifebeforecoffee, Joris_Louwes, Kemm 2, VinothChandar, DeeAshley, brewbooks, craigemorsels, Boris Thaser, Poster Boy NYC, ssoosay, guzzphoto, sachac, chefranden, Wanja Photo, Samuel Petersson, onlyart, samsaundersleeds, Ghita Katz Olsen, mcveja, matthewwu88, Victor Bezrukov, JasonLangheine, erokism, vitroid, thethreesisters, charlywkarl, Sharon & Nikki McCutcheon, Ol.v!er [H2vPk], mikecogh, tec_estromberg, noii's, nicholaspaulsmith, Tucker Sherman, Phil Grondin, Cea., Randomthoughtstome, dcobbinau, rafeejewell, pedrosimoes7, lumaxart, marfis75, roland, RLHyde, David Boyle in DC, Sigfrid Lundberg, Thomas Geiregger, Uberto, bgottsab, Conor Lawless, phphoto2010, Steven | Alan, ckaroli, dweekly, AleBonvini, 드림포유, die.tine, MsSaraKelly, equinoxefr, Sarabbit, Abode of Chaos, Galantucci Alessandro, LadyDragonflyCC - >;< - Spring in Michigan!, Alan Gee, Johan Larsson, SoulRider.222, Robert S. Donovan, amslerPIX, cfaobam, Amy L. Riddle, Bladeflyer, Blomstrom, pumpkincat210, Lord Jim, Symic, kevin dooley, pixelthing, Nelson Minar, Fraser Mummery, The Booklight, edenpictures, everyone's idle, betsyweber, h.koppdelaney, ark, Ben Fredericson (xjrlokix), dphiffer, Jeff Kubina, istolethetv, dullhunk, Tambako the Jaguar, fdecomite, The Daily Ornellas, Badruddeen, kevindooley, mnem, Reyes, sadaton, Mary..K, akunamatata, Dennis Vu Photography for Unleashed Media, mitch98000, ganesha.isis, maria j. luque, doneastwest, w00tdew00t, kevindooley, NightFall404, Infrogmation, nandadevieast, darkpatator, Christos Tsoumplekas, sicamp, Hello Turkey Toe, cliff1066™, James Jordan, gailf548, andrew_byrne, infomatique, graphia, -= Bruce Berrien =-, aphrodite-in-nyc, jmussuto, eiko_eiko, Emily Jane Morgan, _Imaji_, kait jarbeau is in love with you, Leeks, h.koppdelaney, paul-simpson.org, Pinti 1, Namlhots, -KOOPS-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed