|

According to Tony Schwartz, author of The Power of Full Engagement (2004) and Be Excellent at Anything (2011), the optimal learning cycle appears to be approximately ninety minutes of focused concentration. Any more, and your mind and body will naturally need a break. Use that opportunity to exercise, rest, have a meal or snack, take a nap, or do something else.

The First 20 Hours: How to Learn Anything . . . Fast! by Josh Kaufman Build on what you have learned from taking that step. Every time you act, reality changes. If you pay attention, you learn something from taking a smart step. More often than not, it gets you close to what you want. (“I should be able to afford something just outside of downtown.”) Sometimes what you want changes.

In other words, when facing the unknown, act your way into the future that you desire; don’t think your way into it. Thinking does not change reality, nor does it necessarily lead to any learning. You can think all day about starting your businesst, but thinking alone is not going to get you any closer to having one. Just Start: Take Action, Embrace Uncertainty, Create the Future by Leonard A. Schlesinger, Charles F. Kiefer Eliminate barriers to practice.

There are many things that can get in the way of practice, which makes it much more difficult to acquire any skill. Relying on willpower to consistently overcome these barriers is a losing strategy. We only have so much willpower at our disposal each day, and it’s best to use that willpower wisely. The best way to invest willpower in support of skill acquisition is to use it to remove these soft barriers to practice. By rearranging your environment to make it as easy as possible to start practicing, you’ll acquire the skill in far less time. Make dedicated time for practice. The time you spend acquiring a new skill must come from somewhere. If you rely on finding time to do something, it will never be done. If you want to find time, you must make time. You have 24 hours to invest each day: 1,440 minutes, no more or less. You will never have more time. If you sleep approximately 8 hours a day, you have 16 hours at your disposal. Some of those hours will be used to take care of yourself and your loved ones. Others will be used for work. Whatever you have left over is the time you have for skill acquisition. If you want to improve your skills as quickly as possible, the larger the dedicated blocks of time you can set aside, the better. The best approach to making time for skill acquisition is to identify low-value uses of time, then choose to eliminate them. As an experiment, I recommend keeping a simple log of how you spend your time for a few days. All you need is a notebook. The results of this time log will surprise you: if you make a few tough choices to cut low-value uses of time, you’ll have much more time for skill acquisition. The more time you have to devote each day, the less total time it will take to acquire new skills. I recommend making time for at least ninety minutes of practice each day by cutting low-value activities as much as possible. I also recommend precommitting to completing at least twenty hours of practice. Once you start, you must keep practicing until you hit the twenty-hour mark. If you get stuck, keep pushing: you can’t stop until you reach your target performance level or invest twenty hours. If you’re not willing to invest at least twenty hours up front, choose another skill to acquire. Mastery by Robert Greene In Art & Fear (2001), authors David Bayles and Ted Orland share a very interesting anecdote on the value of volume:

The ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups. All those on the left side of the studio, he said, would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right solely on its quality. His procedure was simple: on the final day of class he would bring in his bathroom scales and weigh the work of the “quantity” group: fifty pounds of pots rated an A, forty pounds a B, and so on. Those being graded on “quality,” however, needed to produce only one pot—albeit a perfect one—to get an A. Well, come grading time a curious fact emerged: the works of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity. It seems that while the “quantity” group was busily churning out piles of work and learning from their mistakes, the “quality” group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay. Skill is the result of deliberate, consistent practice, and in early-stage practice, quantity and speed trump absolute quality. The faster and more often you practice, the more rapidly you’ll acquire the skill. Contrary to popular usage, “steep learning curves” are good, not bad. The graph makes it clear why: Steep learning curves indicate a very fast rate of skill acquisition. The steeper the curve, the better you get per unit of time. The First 20 Hours: How to Learn Anything . . . Fast! by Josh Kaufman Karl Popper said many wise things, but I think the following remark is among the wisest: “The best thing that can happen to a human being is to find a problem, to fall in love with that problem, and to live trying to solve that problem, unless another problem even more lovable appears.”

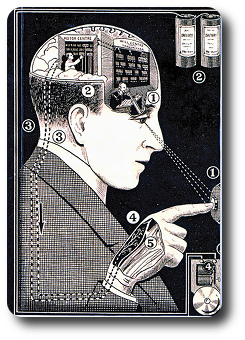

Focus your energy on one skill at a time. One of the easiest mistakes to make when acquiring new skills is attempting to acquire too many skills at the same time. It’s a matter of simple math: acquiring new skills requires a critical mass of concentrated time and focused attention. If you only have an hour or two each day to devote to practice and learning, and you spread that time and energy across twenty different skills, no individual skill is going to receive enough time and energy to generate noticeable improvement. Pick one, and only one, new skill you wish to acquire. Put all of your spare focus and energy into acquiring that skill, and place other skills on temporary hold. David Allen, author of Getting Things Done (2002), recommends establishing what he calls a “someday/maybe” list: a list of things you may want to explore sometime in the future, but that aren’t important enough to focus on right now. I can’t emphasize this enough. Focusing on one prime skill at a time is absolutely necessary for rapid skill acquisition. You’re not giving up on the other skills permanently, you’re just saving them for later. Define your target performance level. A target performance level is a simple sentence that defines what “good enough” looks like. How well would you like to be able to perform the skill you’re acquiring? Deconstruct the skill into subskills. Most of the things we think of as skills are actually bundles of smaller subskills. Once you’ve identified a skill to focus on, the next step is to deconstruct it—to break it down into the smallest possible parts. Deconstructing a skill also makes it easier to avoid feeling overwhelmed. You don’t have to practice all parts of a skill at the same time. Instead, it’s more effective to focus on the subskills that promise the most dramatic overall returns. The First 20 Hours: How to Learn Anything . . . Fast! by Josh Kaufman The human brain is plastic—a term neuroscientists use to indicate that your brain physically changes in response to your environment, your actions, and the consequences of those actions. As you learn any new skill, physical or mental, the neurological wiring of your brain changes as you practice it.

In academic literature, this general process is called the “three-stage model” of skill acquisition,4 and it applies to both physical and mental skills. The three stages are; 1. Cognitive (Early) Stage—understanding what you’re trying to do, researching, thinking about the process, and breaking the skill into manageable parts. 2. Associative (Intermediate) Stage—practicing the task, noticing environmental feedback, and adjusting your approach based on that feedback. 3. Autonomous (Late) Stage—performing the skill effectively and efficiently without thinking about it or paying unnecessary attention to the process. The First 20 Hours: How to Learn Anything . . . Fast! by Josh Kaufman The grammar of language locks us into certain forms of logic and ways of thinking. As the writer Sidney Hook put it, “When Aristotle drew up his table of categories which to him represented the grammar of existence, he was really projecting the grammar of the Greek language on the cosmos.” Linguists have enumerated the high number of concepts that have no particular word to describe them in the English language. If there are no words for certain concepts, we tend to not think of them. And so language is a tool that is often too tight and constricting, compared to the multilayered powers of intelligence we naturally possess.

According to the great mathematician Jacques Hadamard, most mathematicians think in terms of images, creating a visual equivalent of the theorem they are trying to work out. Michael Faraday was a powerful visual thinker. When he came up with the idea of electromagnetic lines of force, anticipating the field theories of the twentieth century, he saw them literally in his mind’s eye before he wrote about them. The structure of the periodic table came to the chemist Dmitry Mendeleyev in a dream, where he literally saw the elements laid out before his eyes in a visual scheme. The list of great thinkers who relied upon images is enormous, and perhaps the greatest of them all was Albert Einstein, who once wrote, “The words of the language, as they are written or spoken, do not seem to play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychical entities which seem to serve as elements in thought are certain signs and more or less clear images which can be voluntarily reproduced and combined.” Studies have indicated that synesthesia is far more prevalent among artists and high-level thinkers. Some have speculated that synesthesia represents a high degree of interconnectivity in the brain, which also plays a role in intelligence. Creative people do not simply think in words, but use all of their senses, their entire bodies in the process. They find sense cues that stimulate their thoughts on many levels—whether it be the smell of something strong, or the tactile feel of a rubber ball. What this means is that they are more open to alternative ways of thinking, creating, and sensing the world. They allow themselves a broader range of sense experience. You must expand as well your notion of thinking and creativity beyond the confines of words and intellectualizations. Stimulating your brain and senses from all directions will help unlock your natural creativity and help revive your original mind. Mastery by Robert Greene Researchers at Stanford University discovered in the 1970s that one of the best ways to combat negative distractions is simply to embrace positive distractions. In short, we can fight bad distractions with good distractions.

In the Stanford study,7 children were given an option to eat one marshmallow right away, or wait a few minutes and receive two marshmallows. The children who were able to delay their gratification employed positive distraction techniques to be successful. Some children sang; others kicked the table; they simply did whatever they needed to do to get their minds focused on something other than the marshmallows. There are many ways to use positive distraction techniques for more than just resisting marshmallows. Set a timer and race the clock to complete a task. Tie unrelated rewards to accomplishments—get a drink from the break room or log on to social media for three minutes after reaching a milestone. Write down every invading and negatively distracting thought and schedule a ten-minute review session later in the day to focus on these anxieties and lay them to rest. Still, it takes a significant amount of self-control to work in a chaotic environment. Ignoring negative distractions to focus on preferred activities requires energy and mental agility. For his book Willpower, psychologist Roy Baumeister analyzed findings from hundreds of experiments to determine why some people can retain focus for hours, while others can’t. He discovered that self-control is not genetic or fixed, but rather a skill one can develop and improve with practice. Baumeister suggests many strategies for increasing self-control. One of these strategies is to develop a seemingly unrelated habit, such as improving your posture or saying “yes” instead of “yeah” or flossing your teeth every night before bed. This can strengthen your willpower in other areas of your life. Additionally, once the new habit is ingrained and can be completed without much effort or thought, that energy can then be turned to other activities requiring more self-control. Tasks done on autopilot don’t use up our stockpile of energy like tasks that have to be consciously completed. Entertaining activities, such as playing strategic games that require concentration and have rules that change as the game advances, or listening to audio books that require attention to follow along with the plot, can also be used to increase attention. Even simple behaviors like regularly getting a good night’s sleep are shown to improve focus and self-control. Manage Your Day-to-Day: Build Your Routine, Find Your Focus, and Sharpen Your Creative Mind (The 99U Book Series) by Jocelyn K. Glei As you work to free up your mind and give it the power to alter its perspective, remember the following: the emotions we experience at any time have an inordinate influence on how we perceive the world.

If we feel afraid, we tend to see more of the potential dangers in some action. If we feel particularly bold, we tend to ignore the potential risks. What you must do then is not only alter your mental perspective, but reverse your emotional one as well. For instance, if you are experiencing a lot of resistance and setbacks in your work, try to see this as in fact something that is quite positive and productive. These difficulties will make you tougher and more aware of the flaws you need to correct. In physical exercise, resistance is a way to make the body stronger, and it is the same with the mind. Play a similar reversal on good fortune—seeing the potential dangers of becoming soft, addicted to attention, and so forth. These reversals will free up the imagination to see more possibilities, which will affect what you do. If you see setbacks as opportunities, you are more likely to make that a reality. Mastery by Robert Greene When Leonardo da Vinci wanted to create a whole new style of painting, one that was more lifelike and emotional, he engaged in an obsessive study of details. He spent endless hours experimenting with forms of light hitting various geometrical solids, to test how light could alter the appearance of objects. He devoted hundreds of pages in his notebooks to exploring the various gradations of shadows in every possible combination. He gave this same attention to the folds of a gown, the patterns in hair, the various minute changes in the expression of a human face. When we look at his work we are not consciously aware of these efforts on his part, but we feel how much more alive and realistic his paintings are, as if he had captured reality.

The average person does not generally pay attention to what we shall call negative cues, what should have happened but did not. It is our natural tendency to fixate on positive information, to notice only what we can see and hear. In business, the natural tendency is to look at what is already out there in the marketplace and to think of how we can make it better or cheaper. The real trick—the equivalent of seeing the negative cue—is to focus our attention on some need that is not currently being met, on what is absent. This requires more thinking and is harder to conceptualize, but the rewards can be immense if we hit upon this unfulfilled need. One interesting way to begin such a thought process is to look at new and available technology in the world and to imagine how it could be applied in a much different way, meeting a need that we sense exists but that is not overly apparent. If the need is too obvious, others will already be working on it. Mastery by Robert Greene |

Click to set custom HTML

Categories

All

Disclosure of Material Connection:

Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.” |

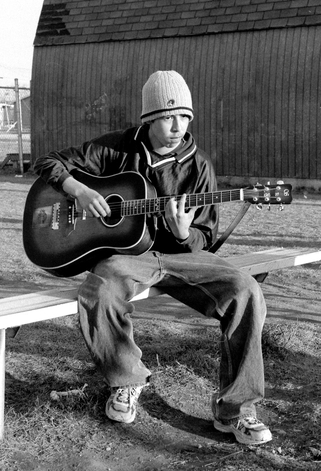

Photos from Wesley Oostvogels, Thomas Leuthard, swanksalot, Robert Scoble, Lord Jim, Pink Sherbet Photography, jonrawlinson, MonsterVinVin, M. Pratter, greybeard39, Stepan Mazurov, deanmeyersnet, Patrick Hoesly, Lord Jim, Dcysiv Moment, fdecomite, h.koppdelaney, Abode of Chaos, pasa47, gagilas, BAMCorp, cmjcool, Abode of Chaos, faith goble, nerdcoregirl, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, jmussuto, Easternblot, Jeanne Menjoulet & Cie, aguscr, h.koppdelaney, Saad Faruque, ups2006, Unai_Guerra, erokism, MsSaraKelly, Jem Yoshioka, tony.cairns, david drexler, Reckless Dream Photography, Raffaele1950, kevin dooley, weegeebored, Cast a Line, Zach Dischner, Eddi van W., kmardahl, faungg's photo, Alan Light, acme, Evan Courtney, specialoperations, Mustafa Khayat, darkday., Orin Zebest, Robert S. Donovan, disparkys, kennethkonica, aubergene, Nina Matthews Photography, infomatique, Patrick Hoesly, j0sh (www.pixael.com), SmithGreg, brewbooks, tjsander, The photographer known as Obi, Simone Ramella, striatic, jmussuto, m.a.r.c., jfinnirwin, Nina J. G., pellesten, dreamsjung, misselejane, Design&Joy, eeskaatt, Bravo_Zulu_, No To the Bike Parking Tax, Kecko, quinn.anya, pedrosimoes7, tanakawho, visualpanic, Brooke Hoyer, Barnaby, Fountain_Head, tripandtravelblog, geishaboy500, gordontarpley, Rising Damp, Marc Aubin2009, belboo, torbakhopper, JarleR, aakanayev, santiago nicolau, Official U.S. Navy Imagery, chinnian, GS+, andreasivarsson, paulswansen, victoriapeckham, Thomas8047, timsamoff, ConvenienceStoreGourmet, Jrwooley6, DeeAshley, ethermoon, torbakhopper, Mark Ramsay, dustin larimer, shannonkringen, Stf.O, Todd Huffman, B Rosen, Lord Jim, Jolene4ever, Ben K Adams, Clearly Ambiguous, Daniele Zedda, Ryan Vaarsi, MsSaraKelly, icebrkr, jauhari, ajeofj3, jenny downing, Joi, GollyGforce, Andrew from Sydney, Lord Jim, 'Retard' (says University of Missouri), drukelly, Sullivan Ng, jdxyw, infomatique, AlicePopkorn, RAA408, Abode of Chaos, SaMaNTHa NiGhTsKy, as always..., D@LY3D, Angelo González, the sugary smell of springtime!, Marko Milošević, pedrosimoes7, MartialArtsNomad.com, 401(K) 2013, Sigfrid Lundberg, MoneyBlogNewz, NBphotostream, the stag and doe, Jemima G, bablu121, .reid., jared, EastsideRJ, Alex Alvisi, Marie A.-C., geishaboy500, modomatic, starsnostars., Hardleers, Sarah G..., donielle, Danny PiG, bigcityal, || UggBoy♥UggGirl || PHOTO || WORLD || TRAVEL ||, -KOOPS-, seafaringwoman, kingkongirl, Richard Masoner / Cyclelicious, Hans Gotun, gruntzooki, Duru..., Vectorportal, Peter Hellberg, Alexandre Hamada Possi, Santi Siri, Joshua Rappeneker, a little tune, Patricia Mangual, erokism, woodleywonderworks, Philippe Put, Purple Sherbet Photography, Abode of Chaos, greybeard39, swanksalot, greyloch, Omarukai, Marc_Smith, SLPTWRK, Peter Alfred Hess, illum, MarioMancuso, willc2, _titi, Lightsurgery, Rennett Stowe, feverblue, Esteman., Keith Allison, DCist, h.koppdelaney, Mike Deal aka ZoneDancer, Jos Dielis, The Wandering Angel, Nathaniel KS, MsSaraKelly, Frank Lindecke, Kara Allyson, JeremyGeorge, deoman56, gagilas, Xoan Baltar, Luke Lawreszuk, Eric-P, fdecomite, lorenkerns, masochismtango, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, anarchosyn, -= Bruce Berrien =-, radiant guy, Free Grunge Textures - www.freestock.ca, El Bibliomata, antmoose, Pedro Belleza, Fitsum Belay/iLLIMETER, Nathan O'Nions, denise carbonell, swanksalot, ▓▒░ TORLEY ░▒▓, Marco Gomes, Justin Ornellas, jenni from the block, René Pütsch, eddieq, thombo2, Ben Mortimer Photography, :moolah, ideowl, joaquinuy, wiredforlego, Rafa G. _, derrickcollins, Fishyone1, ben pollard, Admiralspalast Berlin, Georgio, garybirnie.co.uk, fiskfisk, MoreFunkThanYou, xJason.Rogersx, kevin dooley, David Holmes2, Kris Krug, JD Hancock, Images_of_Money, andriux-uk events, Tyfferz, decafinata, jonrawlinson, isado, Lohan Gunaweera, Derek Mindler, Mike "Dakinewavamon" Kline, themostinept, kiwanja, erokism, dktrpepr, Keoni Cabral, denise carbonell, Neal., tonystl, ericmay, Ally Mauro, erokism, Georgie Pauwels, anitakhart, Ivan Zuber, r2hox, Aka Hige, badjonni, striatic, Arry_B, 401(K) 2012, pvera, Lord Jim, Dredrk aka Mr Sky, TerryJohnston, eschipul, wiredforlego, Yuliya Libkina, fabbio, Justin Ruckman, David Boyle, Matthew Oliphant, Keoni Cabral, Thaddeus Maximus, Abode of Chaos, matthias hämmerly, dospaz, LadyDragonflyCC - >;<, CassiusCassini2011, Abode of Chaos, Jorge Luis Perez, infomatique, Mark Gstohl, AliceNWondrlnd, ç嬥x, ssoosay, striatic, NASA Goddard Photo and Video, feverblue, MsSaraKelly, kohlmann.sascha, Vox Efx, country_boy_shane, paularps, Gage Skidmore, HawkinsSteven, Cam Switzer, Arenamontanus, anieto2k, Georgie Pauwels, my camera and me, Lord Jim, nolifebeforecoffee, Joris_Louwes, Kemm 2, VinothChandar, DeeAshley, brewbooks, craigemorsels, Boris Thaser, Poster Boy NYC, ssoosay, guzzphoto, sachac, chefranden, Wanja Photo, Samuel Petersson, onlyart, samsaundersleeds, Ghita Katz Olsen, mcveja, matthewwu88, Victor Bezrukov, JasonLangheine, erokism, vitroid, thethreesisters, charlywkarl, Sharon & Nikki McCutcheon, Ol.v!er [H2vPk], mikecogh, tec_estromberg, noii's, nicholaspaulsmith, Tucker Sherman, Phil Grondin, Cea., Randomthoughtstome, dcobbinau, rafeejewell, pedrosimoes7, lumaxart, marfis75, roland, RLHyde, David Boyle in DC, Sigfrid Lundberg, Thomas Geiregger, Uberto, bgottsab, Conor Lawless, phphoto2010, Steven | Alan, ckaroli, dweekly, AleBonvini, 드림포유, die.tine, MsSaraKelly, equinoxefr, Sarabbit, Abode of Chaos, Galantucci Alessandro, LadyDragonflyCC - >;< - Spring in Michigan!, Alan Gee, Johan Larsson, SoulRider.222, Robert S. Donovan, amslerPIX, cfaobam, Amy L. Riddle, Bladeflyer, Blomstrom, pumpkincat210, Lord Jim, Symic, kevin dooley, pixelthing, Nelson Minar, Fraser Mummery, The Booklight, edenpictures, everyone's idle, betsyweber, h.koppdelaney, ark, Ben Fredericson (xjrlokix), dphiffer, Jeff Kubina, istolethetv, dullhunk, Tambako the Jaguar, fdecomite, The Daily Ornellas, Badruddeen, kevindooley, mnem, Reyes, sadaton, Mary..K, akunamatata, Dennis Vu Photography for Unleashed Media, mitch98000, ganesha.isis, maria j. luque, doneastwest, w00tdew00t, kevindooley, NightFall404, Infrogmation, nandadevieast, darkpatator, Christos Tsoumplekas, sicamp, Hello Turkey Toe, cliff1066™, James Jordan, gailf548, andrew_byrne, infomatique, graphia, -= Bruce Berrien =-, aphrodite-in-nyc, jmussuto, eiko_eiko, Emily Jane Morgan, _Imaji_, kait jarbeau is in love with you, Leeks, h.koppdelaney, paul-simpson.org, Pinti 1, Namlhots, -KOOPS-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed