|

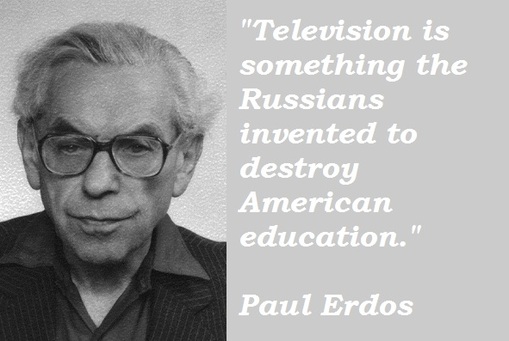

Paul Erdos (1913–1996) Erdos was one of the most brilliant and prolific mathematicians of the twentieth century. He was also, as Paul Hoffman documents in his book The Man Who Loved Only Numbers, a true eccentric—a “mathematical monk” who lived out of a pair of suitcases, dressed in tattered suits, and gave away almost all the money he earned, keeping just enough to sustain his meager lifestyle; a hopeless bachelor who was extremely (perhaps abnormally) devoted to his mother and never learned to cook or even boil his own water for tea; and a fanatic workaholic who routinely put in nineteen-hour days, sleeping only a few hours a night.

Erdos liked to work in short, intense collaborations with other mathematicians, and he crisscrossed the globe seeking fresh talent, often camping out in colleagues’ homes while they worked on a problem together. One such colleague remembered an Erdos visit from the 1970s: … he only needed three hours of sleep. He’d get up early and write letters, mathematical letters. He’d sleep downstairs. The first time he stayed, the clock was set wrong. It said 7:00, but it was really 4:30 A.M. He thought we should be up working, so he turned on the TV full blast. Later, when he knew me better, he’d come up at some early hour and tap on the bedroom door. “Ralph, do you exist?” The pace was grueling. He’d want to work from 8:00 A.M. until 1:30 A.M. Sure we’d break for short meals but we’d write on napkins and talk math the whole time. He’d stay a week or two and you’d collapse at the end. Erdos owed his phenomenal stamina to amphetamines—he took ten to twenty milligrams of Benzedrine or Ritalin daily. Worried about his drug use, a friend once bet Erdoos that he wouldn’t be able to give up amphetamines for a month. Erdos took the bet and succeeded in going cold turkey for thirty days. When he came to collect his money, he told his friend, “You’ve showed me I’m not an addict. But I didn’t get any work done. I’d get up in the morning and stare at a blank piece of paper. I’d have no ideas, just like an ordinary person. You’ve set mathematics back a month.” After the bet, Erdos promptly resumed his amphetamine habit, which he supplemented with shots of strong espresso and caffeine tablets. “A mathematician,” he liked to say, “is a machine for turning coffee into theorems.” Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey Georges Simenon was one of the most prolific novelists of the twentieth century, publishing 425 books in his career, including more than 200 works of pulp fiction under 16 different pseudonyms, as well as 220 novels in his own name and three volumes of autobiography. Remarkably, he didn’t write every day.

The Belgian-French novelist worked in intense bursts of literary activity, each lasting two or three weeks, separated by weeks or months of no writing at all. Even during his productive weeks, Simenon didn’t write for very long each day. His typical schedule was to wake at 6:00 A.M., procure coffee, and write from 6:30 to 9:30. Then he would go for a long walk, eat lunch at 12:30, and take a one-hour nap. In the afternoon he spent time with his children and took another walk before dinner, television, and bed at 10:00 P.M. Simenon liked to portray himself as a methodical writing machine—he could compose up to eighty typed pages in a session, making virtually no revisions after the fact—but he did have his share of superstitious behaviors. No one ever saw him working; the “Do Not Disturb” sign he hung on his door was to be taken seriously. He insisted on wearing the same clothes throughout the composition of each novel. He kept tranquilizers in his shirt pocket, in case he needed to ease the anxiety that beset him at the beginning of each new book. And he weighed himself before and after every book, estimating that each one cost him nearly a liter and a half of sweat. Simenon’s astonishing literary productivity was matched, or even surpassed, in one other area of his daily life—his sexual appetite. “Most people work every day and enjoy sex periodically,” Patrick Marnham notes in his biography of the writer. “Simenon had sex every day and every few months indulged in a frenzied orgy of work.” When living in Paris, Simenon frequently slept with four different women in the same day. He estimated that he bedded ten thousand women in his life. (His second wife disagreed, putting the total closer to twelve hundred.) He explained his sexual hunger as the result of “extreme curiosity” about the opposite sex: “Women have always been exceptional people for me whom I have vainly tried to understand. It has been a lifelong, ceaseless quest. And how could I have created dozens, perhaps hundreds, of female characters in my novels if I had not experienced those adventures which lasted for two hours or ten minutes?” Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey It was a brilliant strategy.

Instead of learning how to survive in just one or two ecological niches, we took on the entire globe. Those unable to rapidly solve new problems or learn from mistakes didn’t survive long enough to pass on their genes. The net effect of this evolution was that we didn’t become stronger; we became smarter. We learned to grow our fangs not in the mouth but in the head. This turned out to be a pretty savvy strategy. We went on to conquer the small rift valleys in Eastern Africa. Then we took over the world. Variability Selection Theory predicts some fairly simple things about human learning. It predicts there will be interactions between two powerful features of the brain: a database in which to store a fund of knowledge, and the ability to improvise off of that database. One allows us to know when we’ve made mistakes. The other allows us to learn from them. Both give us the ability to add new information under rapidly changing conditions. Both may be relevant to the way we design classrooms and cubicles. Any learning environment that deals with only the database instincts or only the improvisatory instincts ignores one half of our ability. It is doomed to fail. It makes me think of jazz guitarists: They’re not going to make it if they know a lot about music theory but don’t know how to jam in a live concert. Some schools and workplaces emphasize a stable, rote-learned database. They ignore the improvisatory instincts drilled into us for millions of years. Creativity suffers. Others emphasize creative usage of a database, without installing a fund of knowledge in the first place. They ignore our need to obtain a deep understanding of a subject, which includes memorizing and storing a richly structured database. You get people who are great improvisers but don’t have depth of knowledge. You may know someone like this where you work. They may look like jazz musicians and have the appearance of jamming, but in the end they know nothing. They’re playing intellectual air guitar. Brain Rules: 12 Principles for Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home, and School by John Medina “I like things to be orderly,” Lynch told a reporter in 1990.

For seven years I ate at Bob’s Big Boy. I would go at 2:30, after the lunch rush. I ate a chocolate shake and four, five, six, seven cups of coffee—with lots of sugar. And there’s lots of sugar in that chocolate shake. It’s a thick shake. In a silver goblet. I would get a rush from all this sugar, and I would get so many ideas! I would write them on these napkins. It was like I had a desk with paper. All I had to do was remember to bring my pen, but a waitress would give me one if I remembered to return it at the end of my stay. I got a lot of ideas at Bob’s. Lynch’s other means of getting ideas is Transcendental Meditation, which he has practiced daily since 1973. “I have never missed a meditation in thirty-three years,” he wrote in his 2006 book, Catching the Big Fish. “I meditate once in the morning and again in the afternoon, for about twenty minutes each time. Then I go about the business of my day.” If he’s shooting a film, he will sometimes sneak in a third session at the end of the day. “We waste so much time on other things, anyway,” he writes. “Once you add this and have a routine, it fits in very naturally.” Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey Routine and physical strength are as necessary as artistic sensitivity to create great work.5/9/2013

When he is writing a novel, Murakami wakes at 4:00 A.M. and works for five to six hours straight. In the afternoons he runs or swims (or does both), runs errands, reads, and listens to music; bedtime is 9:00. “I keep to this routine every day without variation,” he told The Paris Review in 2004. “The repetition itself becomes the important thing; it’s a form of mesmerism. I mesmerize myself to reach a deeper state of mind.”

Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey Murakami has said that maintaining this repetition for the time required to complete a novel takes more than mental discipline: “Physical strength is as necessary as artistic sensitivity.” When he first hung out his shingle as a professional writer, in 1981, after several years running a small jazz club in Tokyo, he discovered that the sedentary lifestyle caused him to gain weight rapidly; he was also smoking as many as sixty cigarettes a day. He soon resolved to change his habits completely, moving with his wife to a rural area, quitting smoking, drinking less, and eating a diet of mostly vegetables and fish. He also started running daily, a habit he has kept up for more than a quarter century. The one drawback to this self-made schedule, Murakami admitted in a 2008 essay, is that it doesn’t allow for much of a social life. “People are offended when you repeatedly turn down their invitations,” he wrote. But he decided that the indispensable relationship in his life was with his readers. “My readers would welcome whatever life style I chose, as long as I made sure each new work was an improvement over the last. And shouldn’t that be my duty—and my top priority—as a novelist?” Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey The book’s title is Daily Rituals, but my focus in writing it was really people’s routines. The word connotes ordinariness and even a lack of thought; to follow a routine is to be on autopilot. But one’s daily routine is also a choice, or a whole series of choices. In the right hands, it can be a finely calibrated mechanism for taking advantage of a range of limited resources: time (the most limited resource of all) as well as willpower, self-discipline, optimism. A solid routine fosters a well-worn groove for one’s mental energies and helps stave off the tyranny of moods. This was one of William James’s favorite subjects. He thought you wanted to put part of your life on autopilot; by forming good habits, he said, we can “free our minds to advance to really interesting fields of action.”

Writing it, I often thought of a line from a letter Kafka sent to his beloved Felice Bauer in 1912. Frustrated by his cramped living situation and his deadening day job, he complained, “time is short, my strength is limited, the office is a horror, the apartment is noisy, and if a pleasant, straightforward life is not possible then one must try to wriggle through by subtle maneuvers.” Poor Kafka! But then who among us can expect to live a pleasant, straightforward life? “A modern stoic,” he observed, “knows that the surest way to discipline passion is to discipline time: decide what you want or ought to do during the day, then always do it at exactly the same moment every day, and passion will give you no trouble.” Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey I can tell you that, despite what cultural pundits might say, creativity—as its been defined by our culture with its endless parade of formulaic novels, memoirs, and films—is the thing to flee from, not only as a member of the “creative class” but also as a member of the “artistic class.” Living when technology is changing the rules of the game in every aspect of our lives, it’s time to question and tear down such clichés and lay them out on the floor in front of us, then reconstruct these smoldering embers into something new, something contemporary, something—finally—relevant.

Careers and canons won’t be established in traditional ways. I’m not so sure that we’ll still have careers in the same way we used to. Literary works might function the same way that memes do today on the Web, spreading like wildfire for a short period, often unsigned and unauthored, only to be supplanted by the next ripple. While the author won’t die, we might begin to view authorship in a more conceptual way: perhaps the best authors of the future will be ones who can write the best programs with which to manipulate, parse and distribute language-based practices. Even if, as Bök claims, poetry in the future will be written by machines for other machines to read, there will be, for the foreseeable future, someone behind the curtain inventing those drones; so that even if literature is reducible to mere code—an intriguing idea—the smartest minds behind them will be considered our greatest authors. With the rise of the Web, writing has met its photography. By that, I mean writing has encountered a situation similar to what happened to painting with the invention of photography, a technology so much better at replicating reality that, in order to survive, painting had to alter its course radically. While traditional notions of writing are primarily focused on “originality” and “creativity,” the digital environment fosters new skill sets that include “manipulation” and “management” of the heaps of already existent and ever-increasing language. What we take to be graphics, sounds, and motion in our screen world is merely a thin skin under which resides miles and miles of language. Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age by Kenneth Goldsmith The model goes like this:

You want to learn as many skills as possible, following the direction that circumstances lead you to, but only if they are related to your deepest interests. Like a hacker, you value the process of self-discovery and making things that are of the highest quality. You avoid the trap of following one set career path. You are not sure where this will all lead, but you are taking full advantage of the openness of information, all of the knowledge about skills now at our disposal. You see what kind of work suits you and what you want to avoid at all cost. You move by trial and error. This is how you pass your twenties. You are the programmer of this wide-ranging apprenticeship, within the loose constraints of your personal interests. You are not wandering about because you are afraid of commitment, but because you are expanding your skill base and your possibilities. At a certain point, when you are ready to settle on something, ideas and opportunities will inevitably present themselves to you. When that happens, all of the skills you have accumulated will prove invaluable. You will be the Master at combining them in ways that are unique and suited to your individuality. You may settle on this one place or idea for several years, accumulating in the process even more skills, then move in a slightly different direction when the time is appropriate. In this new age, those who follow a rigid, singular path in their youth often find themselves in a career dead end in their forties, or overwhelmed with boredom. The wide-ranging apprenticeship of your twenties will yield the opposite—expanding possibilities as you get older. Mastery by Robert Greene “A salamander can be only a salamander, an elk an elk, and a bush a bush. True, a bush is complete in its bushness, yet its limits, while not nearly so severe as some foolish men would believe, are fairly obvious. The peasants of Aelfric are like bushes, like salamanders. They were born one thing and will die one thing.

But you . . . you have already been a warrior, a king, and a serf, and from the looks of it, you aren’t through yet. Thus, you have learned the secret of the new direction. That is: A man can be many things. Maybe anything." Jitterbug Perfume by Tom Robbins I like the idea that all ideas need to have actions and facts tied to them. Without that, they are just wishes. No idea, action, business concept should ignore scientific knowledge.

D ‘Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here,’ said Plato to his students, referring to his school, the Academy; and thereafter no philosophy has ever seriously proposed to ignore scientific knowledge. If philosophy, like religion, has its deepest roots in human ‘finiteness’ – the fact that for us mortals time is limited, and that we are the only beings in this world to be fully aware of this fact – it goes without saying that the question of what to do with our time cannot be avoided. As distinct from trees, oysters and rabbits, we think constantly about our relationship to time: about how we are going to spend the next hour or this evening, or the coming year. And sooner or later we are confronted – sometimes due to a sudden event that breaks our daily routine – with the question of what we are doing, what we should be doing, and what we must be doing with our lives – our time – as a whole. This thought process has three distinct stages: a theoretical stage, a moral or ethical stage, and a crowning conclusion as to salvation or wisdom and this leads to two fundamental questions... These two questions – the nature of the world, and the instruments for understanding it at our disposal as humans –"these" constitute the essentials of the theoretical aspect of philosophy. To be a sage, by definition, is neither to aspire to wisdom or seek the condition of being a sage, but simply to live wisely, contentedly and as freely as possible, having finally overcome the fears sparked in us by our own finiteness. To find one’s place in the world, to learn how to live and act, we must first obtain knowledge of the world in which we find ourselves. This is the first task of a philosophical ‘theory’ A Brief History of Thought: A Philosophical Guide to Living by Luc Ferry |

Click to set custom HTML

Categories

All

Disclosure of Material Connection:

Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.” |

Photos from Wesley Oostvogels, Thomas Leuthard, swanksalot, Robert Scoble, Lord Jim, Pink Sherbet Photography, jonrawlinson, MonsterVinVin, M. Pratter, greybeard39, Stepan Mazurov, deanmeyersnet, Patrick Hoesly, Lord Jim, Dcysiv Moment, fdecomite, h.koppdelaney, Abode of Chaos, pasa47, gagilas, BAMCorp, cmjcool, Abode of Chaos, faith goble, nerdcoregirl, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, jmussuto, Easternblot, Jeanne Menjoulet & Cie, aguscr, h.koppdelaney, Saad Faruque, ups2006, Unai_Guerra, erokism, MsSaraKelly, Jem Yoshioka, tony.cairns, david drexler, Reckless Dream Photography, Raffaele1950, kevin dooley, weegeebored, Cast a Line, Zach Dischner, Eddi van W., kmardahl, faungg's photo, Alan Light, acme, Evan Courtney, specialoperations, Mustafa Khayat, darkday., Orin Zebest, Robert S. Donovan, disparkys, kennethkonica, aubergene, Nina Matthews Photography, infomatique, Patrick Hoesly, j0sh (www.pixael.com), SmithGreg, brewbooks, tjsander, The photographer known as Obi, Simone Ramella, striatic, jmussuto, m.a.r.c., jfinnirwin, Nina J. G., pellesten, dreamsjung, misselejane, Design&Joy, eeskaatt, Bravo_Zulu_, No To the Bike Parking Tax, Kecko, quinn.anya, pedrosimoes7, tanakawho, visualpanic, Brooke Hoyer, Barnaby, Fountain_Head, tripandtravelblog, geishaboy500, gordontarpley, Rising Damp, Marc Aubin2009, belboo, torbakhopper, JarleR, aakanayev, santiago nicolau, Official U.S. Navy Imagery, chinnian, GS+, andreasivarsson, paulswansen, victoriapeckham, Thomas8047, timsamoff, ConvenienceStoreGourmet, Jrwooley6, DeeAshley, ethermoon, torbakhopper, Mark Ramsay, dustin larimer, shannonkringen, Stf.O, Todd Huffman, B Rosen, Lord Jim, Jolene4ever, Ben K Adams, Clearly Ambiguous, Daniele Zedda, Ryan Vaarsi, MsSaraKelly, icebrkr, jauhari, ajeofj3, jenny downing, Joi, GollyGforce, Andrew from Sydney, Lord Jim, 'Retard' (says University of Missouri), drukelly, Sullivan Ng, jdxyw, infomatique, AlicePopkorn, RAA408, Abode of Chaos, SaMaNTHa NiGhTsKy, as always..., D@LY3D, Angelo González, the sugary smell of springtime!, Marko Milošević, pedrosimoes7, MartialArtsNomad.com, 401(K) 2013, Sigfrid Lundberg, MoneyBlogNewz, NBphotostream, the stag and doe, Jemima G, bablu121, .reid., jared, EastsideRJ, Alex Alvisi, Marie A.-C., geishaboy500, modomatic, starsnostars., Hardleers, Sarah G..., donielle, Danny PiG, bigcityal, || UggBoy♥UggGirl || PHOTO || WORLD || TRAVEL ||, -KOOPS-, seafaringwoman, kingkongirl, Richard Masoner / Cyclelicious, Hans Gotun, gruntzooki, Duru..., Vectorportal, Peter Hellberg, Alexandre Hamada Possi, Santi Siri, Joshua Rappeneker, a little tune, Patricia Mangual, erokism, woodleywonderworks, Philippe Put, Purple Sherbet Photography, Abode of Chaos, greybeard39, swanksalot, greyloch, Omarukai, Marc_Smith, SLPTWRK, Peter Alfred Hess, illum, MarioMancuso, willc2, _titi, Lightsurgery, Rennett Stowe, feverblue, Esteman., Keith Allison, DCist, h.koppdelaney, Mike Deal aka ZoneDancer, Jos Dielis, The Wandering Angel, Nathaniel KS, MsSaraKelly, Frank Lindecke, Kara Allyson, JeremyGeorge, deoman56, gagilas, Xoan Baltar, Luke Lawreszuk, Eric-P, fdecomite, lorenkerns, masochismtango, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, anarchosyn, -= Bruce Berrien =-, radiant guy, Free Grunge Textures - www.freestock.ca, El Bibliomata, antmoose, Pedro Belleza, Fitsum Belay/iLLIMETER, Nathan O'Nions, denise carbonell, swanksalot, ▓▒░ TORLEY ░▒▓, Marco Gomes, Justin Ornellas, jenni from the block, René Pütsch, eddieq, thombo2, Ben Mortimer Photography, :moolah, ideowl, joaquinuy, wiredforlego, Rafa G. _, derrickcollins, Fishyone1, ben pollard, Admiralspalast Berlin, Georgio, garybirnie.co.uk, fiskfisk, MoreFunkThanYou, xJason.Rogersx, kevin dooley, David Holmes2, Kris Krug, JD Hancock, Images_of_Money, andriux-uk events, Tyfferz, decafinata, jonrawlinson, isado, Lohan Gunaweera, Derek Mindler, Mike "Dakinewavamon" Kline, themostinept, kiwanja, erokism, dktrpepr, Keoni Cabral, denise carbonell, Neal., tonystl, ericmay, Ally Mauro, erokism, Georgie Pauwels, anitakhart, Ivan Zuber, r2hox, Aka Hige, badjonni, striatic, Arry_B, 401(K) 2012, pvera, Lord Jim, Dredrk aka Mr Sky, TerryJohnston, eschipul, wiredforlego, Yuliya Libkina, fabbio, Justin Ruckman, David Boyle, Matthew Oliphant, Keoni Cabral, Thaddeus Maximus, Abode of Chaos, matthias hämmerly, dospaz, LadyDragonflyCC - >;<, CassiusCassini2011, Abode of Chaos, Jorge Luis Perez, infomatique, Mark Gstohl, AliceNWondrlnd, ç嬥x, ssoosay, striatic, NASA Goddard Photo and Video, feverblue, MsSaraKelly, kohlmann.sascha, Vox Efx, country_boy_shane, paularps, Gage Skidmore, HawkinsSteven, Cam Switzer, Arenamontanus, anieto2k, Georgie Pauwels, my camera and me, Lord Jim, nolifebeforecoffee, Joris_Louwes, Kemm 2, VinothChandar, DeeAshley, brewbooks, craigemorsels, Boris Thaser, Poster Boy NYC, ssoosay, guzzphoto, sachac, chefranden, Wanja Photo, Samuel Petersson, onlyart, samsaundersleeds, Ghita Katz Olsen, mcveja, matthewwu88, Victor Bezrukov, JasonLangheine, erokism, vitroid, thethreesisters, charlywkarl, Sharon & Nikki McCutcheon, Ol.v!er [H2vPk], mikecogh, tec_estromberg, noii's, nicholaspaulsmith, Tucker Sherman, Phil Grondin, Cea., Randomthoughtstome, dcobbinau, rafeejewell, pedrosimoes7, lumaxart, marfis75, roland, RLHyde, David Boyle in DC, Sigfrid Lundberg, Thomas Geiregger, Uberto, bgottsab, Conor Lawless, phphoto2010, Steven | Alan, ckaroli, dweekly, AleBonvini, 드림포유, die.tine, MsSaraKelly, equinoxefr, Sarabbit, Abode of Chaos, Galantucci Alessandro, LadyDragonflyCC - >;< - Spring in Michigan!, Alan Gee, Johan Larsson, SoulRider.222, Robert S. Donovan, amslerPIX, cfaobam, Amy L. Riddle, Bladeflyer, Blomstrom, pumpkincat210, Lord Jim, Symic, kevin dooley, pixelthing, Nelson Minar, Fraser Mummery, The Booklight, edenpictures, everyone's idle, betsyweber, h.koppdelaney, ark, Ben Fredericson (xjrlokix), dphiffer, Jeff Kubina, istolethetv, dullhunk, Tambako the Jaguar, fdecomite, The Daily Ornellas, Badruddeen, kevindooley, mnem, Reyes, sadaton, Mary..K, akunamatata, Dennis Vu Photography for Unleashed Media, mitch98000, ganesha.isis, maria j. luque, doneastwest, w00tdew00t, kevindooley, NightFall404, Infrogmation, nandadevieast, darkpatator, Christos Tsoumplekas, sicamp, Hello Turkey Toe, cliff1066™, James Jordan, gailf548, andrew_byrne, infomatique, graphia, -= Bruce Berrien =-, aphrodite-in-nyc, jmussuto, eiko_eiko, Emily Jane Morgan, _Imaji_, kait jarbeau is in love with you, Leeks, h.koppdelaney, paul-simpson.org, Pinti 1, Namlhots, -KOOPS-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed