Failure really can be an asset if what you’re trying to do is improve, learn, or do something new.6/18/2014

Failure really can be an asset if what you’re trying to do is improve, learn, or do something new. It’s the preceding feature of nearly all successes. There’s nothing shameful about being wrong, about changing course. Each time it happens we have new options. Problems become opportunities.

And that means changing the relationship with failure. It means iterating, failing, and improving. Our capacity to try, try, try is inextricably linked with our ability and tolerance to fail, fail, fail. On the path to successful action, we will fail—possibly many times. And that’s okay. It can be a good thing, even. Action and failure are two sides of the same coin. One doesn’t come without the other. What breaks this critical connection down is when people stop acting—because they’ve taken failure the wrong way. When failure does come, ask: What went wrong here? What can be improved? What am I missing? This helps birth alternative ways of doing what needs to be done, ways that are often much better than what we started with. Failure puts you in corners you have to think your way out of. It is a source of breakthroughs. This is why stories of great success are often preceded by epic failure—because the people in them went back to the drawing board. They weren’t ashamed to fail, but spurred on, piqued by it. Sometimes in sports it takes a close loss to finally convince an underdog that they’ve got the ability to compete that competitor that had intimidated (and beat) them for so long. The loss might be painful, but as Franklin put it, it can also instruct. Great entrepreneurs are: never wedded to a position never afraid to lose a little of their investment never bitter or embarrassed never out of the game for long. It’s time you understand that the world is telling you something with each and every failure and action. It’s feedback—giving you precise instructions on how to improve, it’s trying to wake you up from your cluelessness. It’s trying to teach you something. The Obstacle Is the Way: The Timeless Art of Turning Trials into Triumph The highly successful take unbelievable amounts of action. Regardless of what that action looks like, these people rarely do nothing—even when they are on vacation (just ask their spouses or families!). Whether it is by way of getting others to take action for them, getting attention for their products or ideas, or just grinding it out day and night, the successful have been consistently taking high levels of action—before anyone ever heard their names. The unsuccessful talk about a plan for action but never quite get around to doing what they claim they're going to do—at least enough to ever get what they want. Successful people assume that their future achievements rely on investing in actions that may not pay off today but that when taken consistently and persistently over time will sooner or later bear fruit.

Your ability to take action will be a major factor in determining your potential success—and is a discipline that you should spend time on daily. It's not a gift or trait I was “lucky” enough to receive or inherit; it's a habit that must be developed. Laziness and lack of action are ethical issues for me. I don't think it's right or acceptable for me to be lazy. It is not a “character flaw” that's caused by some invented disease, any more than a highly active person is somehow “blessed.” No one is born to sprint or run a marathon any more than some people are born to take more action than others. Action is necessary in order to create success and can be the single defining quality that will enable you to make the list of successful people. No matter who you are or what you've done in life so far, you can develop this habit in order to enhance your success. The 10X Rule: The Only Difference Between Success and Failure The Comfort Zone is supposed to keep your life safe, but what it really does is keep your life small.

A few rare individuals refuse to live limited lives. They drive through tremendous amounts of pain—from rejections and failures to shorter moments of embarrassment and anxiety. They also handle the small, tedious pain required for personal discipline, forcing themselves to do things we all know we should do but don’t—like exercising, eating right, and staying organized. Because they avoid nothing, they can pursue their highest aspirations. They seem more alive than the rest of us. They have something that gives them the strength to endure pain—a sense of purpose. A sense of purpose doesn’t come from thinking about it. It comes from taking action that moves you toward the future. The moment you do this, you activate a force more powerful than the desire to avoid pain. We call this the “Force of Forward Motion. To tap into this force, you need to move relentlessly forward in your own life—only then have you taken on its form. He talked about the subject closest to his heart—football. He was first team All-City, considered the best running back in the area. For whatever reason, he was eager to explain to me how he’d achieved this distinction. What he said shocked me—I can still remember it forty years later. He explained that he wasn’t the fastest back in the city, nor was he the most elusive. There were stronger players, too. But he was still the best in the city, with big-time scholarship offers to prove it. The reason he was the best, he explained, had nothing to do with his physical abilities—it was his attitude about getting hit. He’d demand the ball on the first play from scrimmage and would run at the nearest tackler. He wouldn’t try to fake him out or run out of bounds. He’d run right at him and get hit on purpose, no matter how much it hurt. “When I get up, I feel great, alive. That’s why I’m the best. The other runners are afraid, you can see it in their eyes.” He was right; none of them shared his desire to get crushed by a defender. My first reaction was that he was mad. He lived in a world of constant pain and danger—and he liked it. It was exactly the world I’d spent my young life avoiding. But I couldn’t get his crazy idea out of my mind; if you go right for the pain, you develop superpowers. The more the years went by, the more I found this to be true—and not just in sports. The Tools: 5 Tools to Help You Find Courage, Creativity, and Willpower--and Inspire You to Live Life in Forward Motion The Mirror Exercise

Select a random person, such as a friend, co-worker, or celebrity. How would you describe this person? Make a short list of this individual’s key character qualities. Then put a plus (+) next to the qualities you like and a minus (-) next to the ones you dislike. Now look at the list you’ve created, and read it back to yourself. But this time consider it from the perspective that you’re looking at a list someone else wrote to describe you. You’ll likely gain some new insights about yourself as you recognize that this is a fair representation of what you like and dislike most about yourself. I’ve offered this mirror exercise to many people around the world, and those who apply it are often stunned by what it reveals. I encour -age you to try it for yourself. It only takes a few minutes, and it will help you realize that other people are not so different from you after all. We commonly praise in others what we like most about ourselves, while condemning those qualities we resist facing in ourselves. Inci -dentally, did I mention what a beautiful, brilliant, and loving person you are? Personal Development for Smart People: The Conscious Pursuit of Personal Growth Are your 10 most expensive material possessions the 10 things that add the most value to your life?2/3/2014

Here’s an exercise for you.

Take a moment, write down your 10 most expensive material possessions from the last decade. Things like your car, your house, your jewelry, your furniture, and any other material possessions you own or have owned in the last ten years. The big ticket items. Next to that list, make another top 10 list: 10 things that add the most value to your life. This list might include experiences like catching a sunset with a loved one, watching your kid play baseball, eating dinner with your parents, etc. Be honest with yourself when you’re making these lists. It’s likely that the lists share zero things in common. What if, instead of focusing the majority of your time, attention, and energy on the 10 most expensive material possessions, you shifted your focus towards the 10 things that added the most value to your life? How would that make you feel? How would your life be different a month from now? A year from now? Five years from now? But then we stopped taking it at face value and asked, “What is an anchor?” That question led us to an important discovery about our own lives: an anchor is the thing that keeps a ship at bay, planted in the harbor, stuck in one place, unable to explore the freedom of the sea. Perhaps we were anchored—we knew we weren’t happy with our lives—and perhaps being anchored wasn’t necessarily a good thing. In the course of time, we each identified our own personal anchors—circumstances keeping us from realizing real freedom—and found they were plentiful (Joshua catalogued 83 anchors; Ryan, 54). We discovered big anchors (debt, bad relationships, etc.) and small anchors (superfluous bills, material possessions, etc.) and in time we eliminated the vast majority of those anchors, one by one, documenting our experience in our book, Minimalism: Live a Meaningful Life. It turned out that being anchored was a terrible thing; it kept us from leading the lives we wanted to lead. No, not all our anchors were bad, but the vast majority prevented us from encountering lasting contentment. Simplicity: Essays For decades, psychologists have been studying this phenomenon, called the “mere exposure” principle, which says that people develop a preference for things that are more familiar (i.e., merely being exposed to something makes us view it more positively).

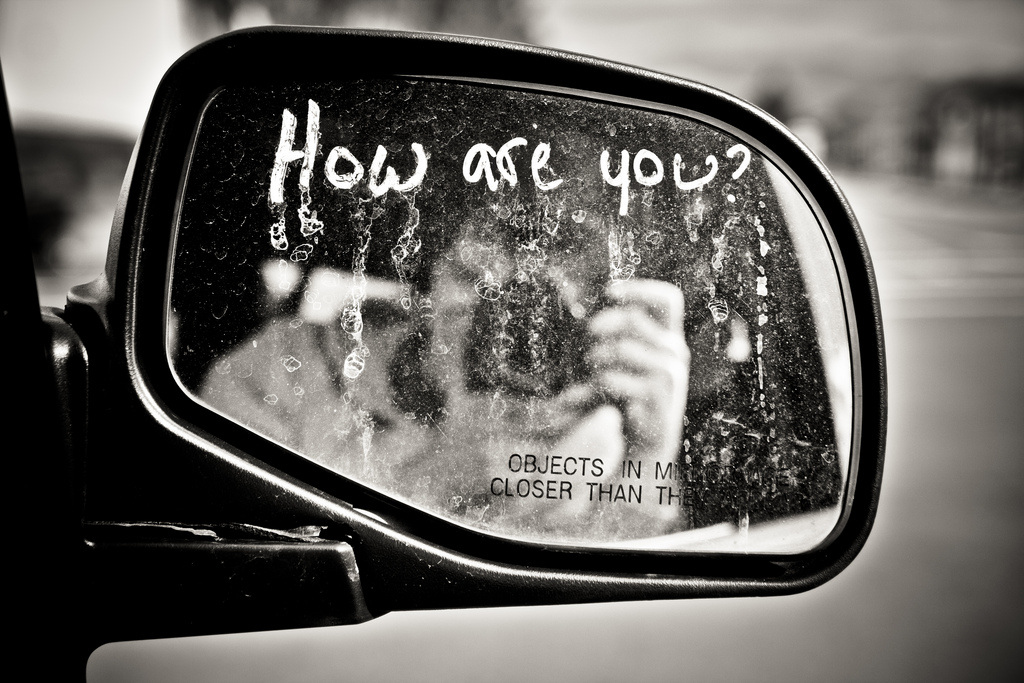

One of the pioneers in the field was Robert Zajonc (whose name now feels strangely likable …). When Zajonc exposed people to various stimuli—nonsense words, Chinese-type characters, photographs of faces—he found that the more they saw the stimuli, the more positive they felt about them. In a fascinating application of this principle, psychologists studied people’s reactions to their own faces. To introduce the study, let’s talk about you for a moment. This may sound odd, but you’re actually not very familiar with your own face. The face you know well is the one you see in the mirror, which of course is the reverse image from what your loved ones see. Knowing this, some clever researchers developed two different photographs of their subjects’ faces: One photo corresponded to their images as seen by everyone else in the world, and the other to their mirror images as seen by them. As predicted by the mere-exposure principle, the subjects preferred the mirror-image photo, and their loved ones preferred the real-image photo. We like our mirror face better than our real face, because it’s more familiar! The face-flipping finding is harmless enough, though weird and surprising. But what’s more troubling is that the mere-exposure principle also extends to our perception of truth. When the participants were exposed to a particular statement three times during the experiment, rather than once, they rated it as more truthful. Repetition sparked trust. Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work We can’t deactivate our biases, but we can counteract them with the right discipline.

1. You encounter a choice. But narrow framing makes you miss options. So Widen Your Options How can you expand your set of choices? We’ll study the habits of people who are expert at uncovering new options, including a college-selection adviser, some executives whose businesses survived (and even thrived) during global recessions, and a boutique firm that has named some of the world’s top brands, including BlackBerry and Pentium. 2. You analyze your options. But the confirmation bias leads you to gather self-serving info. So Reality-Test Your Assumptions. How can you get outside your head and collect information that you can trust? We’ll learn how to ask craftier questions, how to turn a contentious meeting into a productive one in 30 seconds, and what kind of expert advice should make you suspicious. 3. You make a choice. But short-term emotion will often tempt you to make the wrong one. So Attain Distance Before Deciding. How can you overcome short-term emotion and conflicted feelings to make the best choice? We’ll discover how to triumph over manipulative car salesmen, why losing $50 is more painful than gaining $50 is pleasurable, and what simple question often makes agonizing decisions perfectly easy. 4. Then you live with it. But you’ll often be overconfident about how the future will unfold. So Prepare to Be Wrong. How can we plan for an uncertain future so that we give our decisions the best chance to succeed? We’ll show you how one woman scored a raise by mentally simulating the negotiation in advance, how you can rein in your spouse’s crazy business idea, and why it can be smart to warn new employees about how lousy their jobs will be. Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work by Chip Heath, Dan Heath “I must create a system or be enslaved by another man’s; I will not reason and compare: my business is to create.” William Blake

I’m often struck by the way people will toss off the advice to just be yourself without acknowledging that this is a slippery and complicated mission. It requires a vulnerability that our culture has trained us to avoid, so much so that we construct an entire ‘false self’ to protect our tender souls. In order to just be yourself, you have to crack apart that persona and expose the meat of who you are. You need the skills, and enough mastery of your craft, to project that truth of self in your work. When the gap between who you are and the projection of who you are (your ‘personal brand’) is as narrow as possible, you ring true. We call you authentic, and are that much more likely to engage with you or do business with you. That said, I spend a lot of time writing, which is a form of promotion. I do this not to advertise my books or web services, but because I want to help others, and writing is the best way I know how to do it en masse. So my writing is definitely promotion, but that’s a side effect, not a reason I do it. I don’t think I could write good sales copy to save my life. But, I do want to share what I know, and writing information- and opinion-type articles and books is the best way for me to accomplish that goal. Writing also allows me to explore my ideas in public. I don’t usually know if an idea is sound until I write about it. When I share it with someone else, they either agree or look at me sideways. If it’s the latter, I re-evaluate the idea, re-evaluate whether that person is my intended audience, and sometimes I just move on. Everything I Know by Paul Jarvis What this means is simple: language, oral and written, is a relatively recent invention. Well before that time, our ancestors had to learn various skills—toolmaking, hunting, and so forth. The natural model for learning, largely based on the power of mirror neurons, came from watching and imitating others, then repeating the action over and over. Our brains are highly suited for this form of learning.

First, it is essential that you begin with one skill that you can master, and that serves as a foundation for acquiring others. You must avoid at all cost the idea that you can manage learning several skills at a time. You need to develop your powers of concentration, and understand that trying to multitask will be the death of the process. Second, the initial stages of learning a skill invariably involve tedium. Yet rather than avoiding this inevitable tedium, you must accept and embrace it. The pain and boredom we experience in the initial stage of learning a skill toughens our minds, much like physical exercise. Too many people believe that everything must be pleasurable in life, which makes them constantly search for distractions and short-circuits the learning process. The pain is a kind of challenge your mind presents—will you learn how to focus and move past the boredom. Mastery by Robert Greene Goethe had now come to the conclusion that all forms of human knowledge are manifestations of the same life force he had intuited in his near-death experience as a young man. The problem with most people, he felt, is that they build artificial walls around subjects and ideas. The real thinker sees the connections, grasps the essence of the life force operating in every individual instance. Why should any individual stop at poetry, or find art unrelated to science, or narrow his or her intellectual interests? The mind was designed to connect things, like a loom that knits together all of the threads of a fabric. If life exists as an organic whole and cannot be separated into parts without losing a sense of the whole, then thinking should make itself equal to the whole.

A few months later, he wrote his friend, the great linguist and educator Wilhelm von Humboldt, the following: “The human organs, by means of practice, training, reflection, success or failure, furtherance or resistance…learn to make the necessary connections unconsciously, the acquired and the intuitive working hand-in-hand, so that a unison results which is the world’s wonder…The world is ruled by bewildered theories of bewildering operations; and nothing is to me more important than, so far as is possible, to turn to the best account what is in me and persists in me, and keep a firm hand upon my idiosyncrasies.” These would be the last words he would write. Within a few days he was dead, at the age of eighty-three. Mastery by Robert Greene |

Click to set custom HTML

Categories

All

Disclosure of Material Connection:

Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, I only recommend products or services I use personally and believe will add value to my readers. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.” |

Photos from Wesley Oostvogels, Thomas Leuthard, swanksalot, Robert Scoble, Lord Jim, Pink Sherbet Photography, jonrawlinson, MonsterVinVin, M. Pratter, greybeard39, Stepan Mazurov, deanmeyersnet, Patrick Hoesly, Lord Jim, Dcysiv Moment, fdecomite, h.koppdelaney, Abode of Chaos, pasa47, gagilas, BAMCorp, cmjcool, Abode of Chaos, faith goble, nerdcoregirl, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, jmussuto, Easternblot, Jeanne Menjoulet & Cie, aguscr, h.koppdelaney, Saad Faruque, ups2006, Unai_Guerra, erokism, MsSaraKelly, Jem Yoshioka, tony.cairns, david drexler, Reckless Dream Photography, Raffaele1950, kevin dooley, weegeebored, Cast a Line, Zach Dischner, Eddi van W., kmardahl, faungg's photo, Alan Light, acme, Evan Courtney, specialoperations, Mustafa Khayat, darkday., Orin Zebest, Robert S. Donovan, disparkys, kennethkonica, aubergene, Nina Matthews Photography, infomatique, Patrick Hoesly, j0sh (www.pixael.com), SmithGreg, brewbooks, tjsander, The photographer known as Obi, Simone Ramella, striatic, jmussuto, m.a.r.c., jfinnirwin, Nina J. G., pellesten, dreamsjung, misselejane, Design&Joy, eeskaatt, Bravo_Zulu_, No To the Bike Parking Tax, Kecko, quinn.anya, pedrosimoes7, tanakawho, visualpanic, Brooke Hoyer, Barnaby, Fountain_Head, tripandtravelblog, geishaboy500, gordontarpley, Rising Damp, Marc Aubin2009, belboo, torbakhopper, JarleR, aakanayev, santiago nicolau, Official U.S. Navy Imagery, chinnian, GS+, andreasivarsson, paulswansen, victoriapeckham, Thomas8047, timsamoff, ConvenienceStoreGourmet, Jrwooley6, DeeAshley, ethermoon, torbakhopper, Mark Ramsay, dustin larimer, shannonkringen, Stf.O, Todd Huffman, B Rosen, Lord Jim, Jolene4ever, Ben K Adams, Clearly Ambiguous, Daniele Zedda, Ryan Vaarsi, MsSaraKelly, icebrkr, jauhari, ajeofj3, jenny downing, Joi, GollyGforce, Andrew from Sydney, Lord Jim, 'Retard' (says University of Missouri), drukelly, Sullivan Ng, jdxyw, infomatique, AlicePopkorn, RAA408, Abode of Chaos, SaMaNTHa NiGhTsKy, as always..., D@LY3D, Angelo González, the sugary smell of springtime!, Marko Milošević, pedrosimoes7, MartialArtsNomad.com, 401(K) 2013, Sigfrid Lundberg, MoneyBlogNewz, NBphotostream, the stag and doe, Jemima G, bablu121, .reid., jared, EastsideRJ, Alex Alvisi, Marie A.-C., geishaboy500, modomatic, starsnostars., Hardleers, Sarah G..., donielle, Danny PiG, bigcityal, || UggBoy♥UggGirl || PHOTO || WORLD || TRAVEL ||, -KOOPS-, seafaringwoman, kingkongirl, Richard Masoner / Cyclelicious, Hans Gotun, gruntzooki, Duru..., Vectorportal, Peter Hellberg, Alexandre Hamada Possi, Santi Siri, Joshua Rappeneker, a little tune, Patricia Mangual, erokism, woodleywonderworks, Philippe Put, Purple Sherbet Photography, Abode of Chaos, greybeard39, swanksalot, greyloch, Omarukai, Marc_Smith, SLPTWRK, Peter Alfred Hess, illum, MarioMancuso, willc2, _titi, Lightsurgery, Rennett Stowe, feverblue, Esteman., Keith Allison, DCist, h.koppdelaney, Mike Deal aka ZoneDancer, Jos Dielis, The Wandering Angel, Nathaniel KS, MsSaraKelly, Frank Lindecke, Kara Allyson, JeremyGeorge, deoman56, gagilas, Xoan Baltar, Luke Lawreszuk, Eric-P, fdecomite, lorenkerns, masochismtango, Adrian Fallace Design & Photography, anarchosyn, -= Bruce Berrien =-, radiant guy, Free Grunge Textures - www.freestock.ca, El Bibliomata, antmoose, Pedro Belleza, Fitsum Belay/iLLIMETER, Nathan O'Nions, denise carbonell, swanksalot, ▓▒░ TORLEY ░▒▓, Marco Gomes, Justin Ornellas, jenni from the block, René Pütsch, eddieq, thombo2, Ben Mortimer Photography, :moolah, ideowl, joaquinuy, wiredforlego, Rafa G. _, derrickcollins, Fishyone1, ben pollard, Admiralspalast Berlin, Georgio, garybirnie.co.uk, fiskfisk, MoreFunkThanYou, xJason.Rogersx, kevin dooley, David Holmes2, Kris Krug, JD Hancock, Images_of_Money, andriux-uk events, Tyfferz, decafinata, jonrawlinson, isado, Lohan Gunaweera, Derek Mindler, Mike "Dakinewavamon" Kline, themostinept, kiwanja, erokism, dktrpepr, Keoni Cabral, denise carbonell, Neal., tonystl, ericmay, Ally Mauro, erokism, Georgie Pauwels, anitakhart, Ivan Zuber, r2hox, Aka Hige, badjonni, striatic, Arry_B, 401(K) 2012, pvera, Lord Jim, Dredrk aka Mr Sky, TerryJohnston, eschipul, wiredforlego, Yuliya Libkina, fabbio, Justin Ruckman, David Boyle, Matthew Oliphant, Keoni Cabral, Thaddeus Maximus, Abode of Chaos, matthias hämmerly, dospaz, LadyDragonflyCC - >;<, CassiusCassini2011, Abode of Chaos, Jorge Luis Perez, infomatique, Mark Gstohl, AliceNWondrlnd, ç嬥x, ssoosay, striatic, NASA Goddard Photo and Video, feverblue, MsSaraKelly, kohlmann.sascha, Vox Efx, country_boy_shane, paularps, Gage Skidmore, HawkinsSteven, Cam Switzer, Arenamontanus, anieto2k, Georgie Pauwels, my camera and me, Lord Jim, nolifebeforecoffee, Joris_Louwes, Kemm 2, VinothChandar, DeeAshley, brewbooks, craigemorsels, Boris Thaser, Poster Boy NYC, ssoosay, guzzphoto, sachac, chefranden, Wanja Photo, Samuel Petersson, onlyart, samsaundersleeds, Ghita Katz Olsen, mcveja, matthewwu88, Victor Bezrukov, JasonLangheine, erokism, vitroid, thethreesisters, charlywkarl, Sharon & Nikki McCutcheon, Ol.v!er [H2vPk], mikecogh, tec_estromberg, noii's, nicholaspaulsmith, Tucker Sherman, Phil Grondin, Cea., Randomthoughtstome, dcobbinau, rafeejewell, pedrosimoes7, lumaxart, marfis75, roland, RLHyde, David Boyle in DC, Sigfrid Lundberg, Thomas Geiregger, Uberto, bgottsab, Conor Lawless, phphoto2010, Steven | Alan, ckaroli, dweekly, AleBonvini, 드림포유, die.tine, MsSaraKelly, equinoxefr, Sarabbit, Abode of Chaos, Galantucci Alessandro, LadyDragonflyCC - >;< - Spring in Michigan!, Alan Gee, Johan Larsson, SoulRider.222, Robert S. Donovan, amslerPIX, cfaobam, Amy L. Riddle, Bladeflyer, Blomstrom, pumpkincat210, Lord Jim, Symic, kevin dooley, pixelthing, Nelson Minar, Fraser Mummery, The Booklight, edenpictures, everyone's idle, betsyweber, h.koppdelaney, ark, Ben Fredericson (xjrlokix), dphiffer, Jeff Kubina, istolethetv, dullhunk, Tambako the Jaguar, fdecomite, The Daily Ornellas, Badruddeen, kevindooley, mnem, Reyes, sadaton, Mary..K, akunamatata, Dennis Vu Photography for Unleashed Media, mitch98000, ganesha.isis, maria j. luque, doneastwest, w00tdew00t, kevindooley, NightFall404, Infrogmation, nandadevieast, darkpatator, Christos Tsoumplekas, sicamp, Hello Turkey Toe, cliff1066™, James Jordan, gailf548, andrew_byrne, infomatique, graphia, -= Bruce Berrien =-, aphrodite-in-nyc, jmussuto, eiko_eiko, Emily Jane Morgan, _Imaji_, kait jarbeau is in love with you, Leeks, h.koppdelaney, paul-simpson.org, Pinti 1, Namlhots, -KOOPS-

RSS Feed

RSS Feed