|

“It’s not about ideas, it’s about making ideas happen.”

It’s time to stop blaming our surroundings and start taking responsibility. While no workplace is perfect, it turns out that our gravest challenges are a lot more primal and personal. Our individual practices ultimately determine what we do and how well we do it. Specifically, it’s our routine (or lack thereof), our capacity to work proactively rather than reactively, and our ability to systematically optimize our work habits over time that determine our ability to make ideas happen. Through our constant connectivity to each other, we have become increasingly reactive to what comes to us rather than being proactive about what matters most to us. Truly great creative achievements require hundreds, if not thousands, of hours of work, and we have to make time every single day to put in those hours. Routines help us do this by setting expectations about availability, aligning our workflow with our energy levels, and getting our minds into a regular rhythm of creating. At the end of the day—or, really, from the beginning—building a routine is all about persistence and consistency. Don’t wait for inspiration; create a framework for it. CREATIVE WORK FIRST, REACTIVE WORK SECOND The single most important change you can make in your working habits is to switch to creative work first, reactive work second. This means blocking off a large chunk of time every day for creative work on your own priorities, with the phone and e-mail off. I used to be a frustrated writer. Making this switch turned me into a productive writer. Now, I start the working day with several hours of writing. I never schedule meetings in the morning, if I can avoid it. So whatever else happens, I always get my most important work done—and looking back, all of my biggest successes have been the result of making this simple change. But it’s better to disappoint a few people over small things, than to surrender your dreams for an empty inbox. Otherwise you’re sacrificing your potential for the illusion of professionalism. Manage Your Day-to-Day: Build Your Routine, Find Your Focus, and Sharpen Your Creative Mind (The 99U Book Series) by Jocelyn K. Glei Georges Simenon was one of the most prolific novelists of the twentieth century, publishing 425 books in his career, including more than 200 works of pulp fiction under 16 different pseudonyms, as well as 220 novels in his own name and three volumes of autobiography. Remarkably, he didn’t write every day.

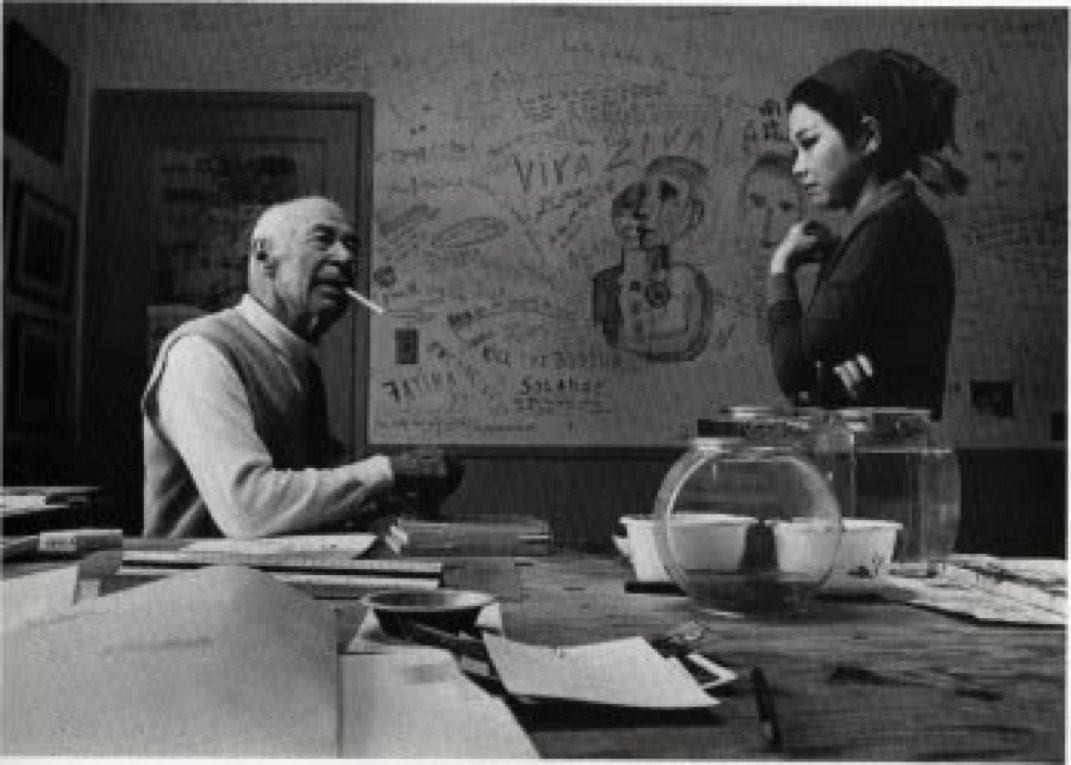

The Belgian-French novelist worked in intense bursts of literary activity, each lasting two or three weeks, separated by weeks or months of no writing at all. Even during his productive weeks, Simenon didn’t write for very long each day. His typical schedule was to wake at 6:00 A.M., procure coffee, and write from 6:30 to 9:30. Then he would go for a long walk, eat lunch at 12:30, and take a one-hour nap. In the afternoon he spent time with his children and took another walk before dinner, television, and bed at 10:00 P.M. Simenon liked to portray himself as a methodical writing machine—he could compose up to eighty typed pages in a session, making virtually no revisions after the fact—but he did have his share of superstitious behaviors. No one ever saw him working; the “Do Not Disturb” sign he hung on his door was to be taken seriously. He insisted on wearing the same clothes throughout the composition of each novel. He kept tranquilizers in his shirt pocket, in case he needed to ease the anxiety that beset him at the beginning of each new book. And he weighed himself before and after every book, estimating that each one cost him nearly a liter and a half of sweat. Simenon’s astonishing literary productivity was matched, or even surpassed, in one other area of his daily life—his sexual appetite. “Most people work every day and enjoy sex periodically,” Patrick Marnham notes in his biography of the writer. “Simenon had sex every day and every few months indulged in a frenzied orgy of work.” When living in Paris, Simenon frequently slept with four different women in the same day. He estimated that he bedded ten thousand women in his life. (His second wife disagreed, putting the total closer to twelve hundred.) He explained his sexual hunger as the result of “extreme curiosity” about the opposite sex: “Women have always been exceptional people for me whom I have vainly tried to understand. It has been a lifelong, ceaseless quest. And how could I have created dozens, perhaps hundreds, of female characters in my novels if I had not experienced those adventures which lasted for two hours or ten minutes?” Daily Rituals: How Artists Work by Mason Currey In moving toward mastery, you are bringing your mind closer to reality and to life itself.

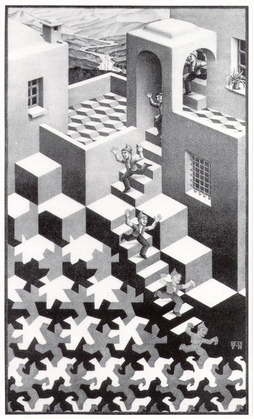

Anything that is alive is in a continual state of change and movement. The moment that you rest, thinking that you have attained the level you desire, a part of your mind enters a phase of decay. You lose your hard-earned creativity and others begin to sense it. This is a power and intelligence that must be continually renewed or it will die. .....Verrocchio instructed his apprentices in all of the sciences that were necessary to produce the work of his studio—engineering, mechanics, chemistry, and metallurgy. Leonardo was eager to learn all of these skills, but soon he discovered in himself something else: he could not simply do an assignment; he needed to make it something of his own, to invent rather than imitate the Master. For Napoleon Bonaparte it was his “star” that he always felt in ascendance when he made the right move. For Socrates, it was his daemon, a voice that he heard, perhaps from the gods, which inevitably spoke to him in the negative—telling him what to avoid. For Goethe, he also called it a daemon—a kind of spirit that dwelled within him and compelled him to fulfill his destiny. In more modern times, Albert Einstein talked of a kind of inner voice that shaped the direction of his speculations. All of these are variations on what Leonardo da Vinci experienced with his own sense of fate Mastery by Robert Greene The 4-Hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich (Expanded and Updated)

by Timothy Ferriss Notes Part 1 This has to be the most requested book here on the site, but it is also one of those books that I think are misunderstood. Where many of the fans of the book picked up on creating a business on a laptop, and working "four hour" weeks, if you read the book closely you see the normal job deconstructed, and a defense of your time. He states at one point, the book is not for people who want to run businesses, it is for those that want to own them. It is for people who want to control their own time. The book is almost a stereotype, but is definitely worth reading. It is one of those books that today it is hard to understand how different it was when it came out, because the book helped make what is the new entrepreneur today. People don’t want to be millionaires—they want to experience what they believe only millions can buy. (Time and experience are the only things that matter.) ..... this book is not about finding your “dream job.” I will take as a given that, for most people, somewhere between six and seven billion of them, the perfect job is the one that takes the least time. The vast majority of people will never find a job that can be an unending source of fulfillment, so that is not the goal here; to free time and automate income is. Reality is negotiable. Outside of science and law, all rules can be bent or broken, and it doesn’t require being unethical. Focus on being productive instead of busy. Conditions are never perfect. If it’s important to you and you want to do it “eventually,” just do it and correct course along the way. If it isn’t going to devastate those around you, try it and then justify it.(Simply said Do. Test. Correct. Do Again.) It is far more lucrative and fun to leverage your strengths instead of attempting to fix all the chinks in your armor. The choice is between multiplication of results using strengths or incremental improvement fixing weaknesses that will, at best, become mediocre. Focus on better use of your best weapons instead of constant repair. People who avoid all criticism fail. Action may not always bring happiness, but there is no happiness without action. —BENJAMIN DISRAELI, former British Prime Minister I realized that on a scale of 1–10, 1 being nothing and 10 being permanently life-changing, my so-called worst-case scenario might have a temporary impact of 3 or 4. I believe this is true of most people and most would-be “holy sh*t, my life is over” disasters. Keep in mind that this is the one-in-a-million disaster nightmare....best-case scenario, or even a probable-case scenario, it would easily have a permanent 9 or 10 positive life-changing effect. In other words, I was risking an unlikely and temporary 3 or 4 for a probable and permanent 9 or 10, and I could easily recover my baseline workaholic prison with a bit of extra work if I wanted to. This all equated to a significant realization: There was practically no risk, only huge life-changing upside potential, and I could resume my previous course without any more effort than I was already putting forth. You have comfort. You don’t have luxury. And don’t tell me that money plays a part. The luxury I advocate has nothing to do with money. It cannot be bought. It is the reward of those who have no fear of discomfort. —JEAN COCTEAU Usually, what we most fear doing is what we most need to do. - (By far my favorite phrase from the book, and one that pops in my head many times a day.) The 4-Hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich (Expanded and Updated) What are you waiting for? If you cannot answer this without resorting to the previously rejected concept of good timing, the answer is simple: You’re afraid, just like the rest of the world. Measure the cost of inaction, realize the unlikelihood and re-pairability of most missteps, and develop the most important habit of those who excel and enjoy Unreasonable and unrealistic goals are easier to achieve for yet another reason. ....fishing is best where the fewest go, and the collective insecurity of the world makes it easy for people to hit home runs while everyone else is aiming for base hits. There is just less competition for bigger goals. Excitement is the more practical synonym for happiness, and it is precisely what you should strive to chase. It is the cure-all. When people suggest you follow your “passion” or your “bliss,” I propose that they are, in fact, referring to the same singular concept: excitement. This brings us full circle. The question you should be asking isn’t, “What do I want?” or “What are my goals?” but “What would excite me?” When I started BrainQUICKEN LLC in 2001, it was with a clear goal in mind: Make $1,000 per day whether I was banging my head on a laptop or cutting my toenails on the beach. It was to be an automated source of cash flow. (Definite specific goals matter) Dreamlining is so named because it applies timelines to what most would consider dreams. It is much like goal-setting but differs in several fundamental respects: The goals shift from ambiguous wants to defined steps. The goals have to be unrealistic to be effective. It focuses on activities that will fill the vacuum created when work is removed. Living like a millionaire requires doing interesting things and not just owning enviable things. Now it’s your turn to think big. ...... The goal is to start a dialogue so they take the time to answer future e-mails—not to ask for help. That can only come after at least three or four genuine e-mail exchanges.” (to meet new people, to get advice) Life is too short to be small. —BENJAMIN DISRAELI Dreamlining (Setting Goals) Create two timelines—6 months and 12 months—and list up to five things you dream of having (including, but not limited to, material wants: house, car, clothing, etc.), being (be a great cook, be fluent in Chinese, etc.), and doing (visiting Thailand, tracing your roots overseas, racing ostriches, etc.) in that order. Do not limit yourself, and do not concern yourself with how these things will be accomplished. For now, it’s unimportant. This is an exercise in reversing repression. If still blocked, fill in the five “doing” spots with the following: one place to visit one thing to do before you die (a memory of a lifetime) one thing to do daily one thing to do weekly one thing you’ve always wanted to learn Convert each “being” into a “doing” to make it actionable. Identify an action that would characterize this state of being or a task that would mean you had achieved it. People find it easier to brainstorm “being” first, but this column is just a temporary holding spot for “doing” actions. Using the 6-month timeline, star or otherwise highlight the four most exciting and/or important dreams from all columns. Repeat the process with the 12-month timeline if desired. Determine the cost of these dreams and calculate your Target Monthly Income (TMI) for both timelines Last, calculate your Target Monthly Income (TMI) for realizing these dreamlines. This is how to do it: First, total each of the columns A, B, and C, counting only the four selected dreams. Some of these column totals could be zero, which is fine. Next, add your total monthly expenses x 1.3 (the 1.3 represents your expenses plus a 30% buffer for safety or savings). This grand total is your TMI and the target to keep in mind for the rest of the book. I like to further divide this TMI by 30 to get my TDI—Target Daily Income. I find it easier to work with a daily goal. Online calculators on our companion site do all the work for you and make this step a cinch. The objective of this exercise isn’t, therefore, to outline every step from start to finish, but to define the end goal, the required vehicle to achieve them (TMI, TDI), and build momentum with critical first steps. From that point, it’s a matter of freeing time and generating the TMI, which the following chapters cover. Once you have three steps for each of the four goals, complete the three actions in the “now” column. Do it now. Each should be simple enough to do in five minutes or less. If not, rachet it down. If it’s the middle of the night and you can’t call someone, do something else now, such as send an e-mail, and set the call for first thing tomorrow. The best first step, the one I recommend, is finding someone who’s done it and ask for advice on how to do the same. It’s not hard. One does not accumulate but eliminate. It is not daily increase but daily decrease. The height of cultivation always runs to simplicity. (Bruce Lee Quote) Effectiveness is doing the things that get you closer to your goals. Efficiency is performing a given task (whether important or not) in the most economical manner possible. I would consider the best door-to-door salesperson efficient—that is, refined and excellent at selling door-to-door without wasting time—but utterly ineffective. He or she would sell more using a better vehicle such as e-mail or direct mail. Here are two truisms to keep in mind: Doing something unimportant well does not make it important. Requiring a lot of time does not make a task important. What you do is infinitely more important than how you do it. Efficiency is still important, but it is useless unless applied to the right things. Pareto’s Law can be summarized as follows: 80% of the outputs result from 20% of the inputs. 80% of the consequences flow from 20% of the causes. 80% of the results come from 20% of the effort and time. 80% of company profits come from 20% of the products and customers. 80% of all stock market gains are realized by 20% of the investors and 20% of an individual portfolio The next morning, I began a dissection of my business and personal life through the lenses of two questions: Which 20% of sources are causing 80% of my problems and unhappiness? Which 20% of sources are resulting in 80% of my desired outcomes and happiness? Make no mistake, maximum income from minimal necessary effort (including minimum number of customers) is the primary goal. I duplicated my strengths, in this case my top producers, and focused on increasing the size and frequency of their orders. Slow down and remember this: Most things make no difference. Being busy is a form of laziness—lazy thinking and indiscriminate action Being overwhelmed is often as unproductive as doing nothing, and is far more unpleasant. Being selective—doing less—is the path of the productive. Focus on the important few and ignore the rest. .....the key to not feeling rushed is remembering that lack of time is actually lack of priorities You don’t need 8 hours per day to become a legitimate millionaire—let alone have the means to live like one. Parkinson’s Law dictates that a task will swell in (perceived) importance and complexity in relation to the time allotted for its completion. It is the magic of the imminent deadline. There are two synergistic approaches for increasing productivity that are inversions of each other: Limit tasks to the important to shorten work time (80/20). Shorten work time to limit tasks to the important (Parkinson’s Law). The best solution is to use both together: Identify the few critical tasks that contribute most to income and schedule them with very short and clear deadlines. If you haven’t identified the mission-critical tasks and set aggressive start and end times for their completion, the unimportant becomes the important. Even if you know what’s critical, without deadlines that create focus, the minor tasks forced upon you (or invented, in the case of the entrepreneur) will swell to consume time until another bit of minutiae jumps in to replace it, leaving you at the end of the day with nothing accomplished. I just asked him to do one simple thing consistently without fail. At least three times per day at scheduled times, he had to ask himself the following question: Am I being productive or just active? Charney captured the essence of this with less-abstract wording: Am I inventing things to do to avoid the important? 6. Learn to ask, “If this is the only thing I accomplish today, will I be satisfied with my day?” Compile your to-do list for tomorrow no later than this evening. I don’t recommend using Outlook or computerized to-do lists, because it is possible to add an infinite number of items. I use a standard piece of paper folded in half three times, which fits perfectly in the pocket and limits you to noting only a few items. There should never be more than two mission-critical items to complete each day. Never. It just isn’t necessary if they’re actually high-impact. If you are stuck trying to decide between multiple items that all seem crucial, as happens to all of us, look at each in turn and ask yourself, If this is the only thing I accomplish today, will I be satisfied with my day? Reading, after a certain age, diverts the mind too much from its creative pursuits. Any man who reads too much and uses his own brain too little falls into lazy habits of thinking. —ALBERT EINSTEIN From an actionable information standpoint, I consume a maximum of one-third of one industry magazine (Response magazine) and one business magazine (Inc.) per month, for a grand total of approximately four hours. That’s it for results-oriented reading. I read an hour of fiction prior to bed for relaxation. (I truly believe he reads much more than this.) 1. I picked one book out of dozens based on reader reviews and the fact that the authors had actually done what I wanted to do. If the task is how-to in nature, I only read accounts that are “how I did it” and autobiographical. No speculators or wannabes are worth the time. 2. Using the book to generate intelligent and specific questions, I contacted 10 of the top authors and agents in the world via e-mail and phone, with a response rate of 80%. How to Read 200% Faster in 10 Minutes 1. Two Minutes: Use a pen or finger to trace under each line as you read as fast as possible. Reading is a series of jumping snapshots (called saccades), and using a visual guide prevents regression. 2. Three Minutes: Begin each line focusing on the third word in from the first word, and end each line focusing on the third word in from the last word. This makes use of peripheral vision that is otherwise wasted on margins. For example, even when the highlighted words in the next line are your beginning and ending focal points, the entire sentence is “read,” just with less eye movement: 3. Two Minutes: Once comfortable indenting three or four words from both sides, attempt to take only two snapshots—also known as fixations—per line on the first and last indented words. 4. Three Minutes: Practice reading too fast for comprehension but with good technique (the above three techniques) for five pages prior to reading at a comfortable speed. This will heighten perception and reset your speed limit, much like how 50 mph normally feels fast but seems like slow motion if you drop down from 70 mph on the freeway. Develop the habit of asking yourself, “Will I definitely use this information for something immediate and important?” .....complete your most important task before 11:00 A.M. to avoid using lunch or reading e-mail as a postponement excuse Create systems to limit your availability via e-mail and phone and deflect inappropriate contact. Batch activities to limit setup cost and provide more time for dreamline milestones. Set or request autonomous rules and guidelines with occasional review of results. Here is a sneak preview of full automation. I woke up this morning, and given that it’s Monday, I checked my e-mail for one hour after an exquisite Buenos Aires breakfast. Sowmya from India had found a long-lost high school classmate of mine, and Anakool from YMII had put together Excel research reports for retiree happiness and the average annual hours worked in different fields. Interviews for this week had been set by a third Indian virtual assistant, who had also found contact information for the best Kendo schools in Japan and the top salsa teachers in Cuba. In the next e-mail folder, I was pleased to see that my fulfillment account manager in Tennessee, Beth, had resolved nearly two dozen problems in the last week—keeping our largest clients in China and South Africa smiling—and had also coordinated California sales tax filing with my accountants in Michigan. The taxes had been paid via my credit card on file, and a quick glance at my bank accounts confirmed that Shane and the rest of the team at my credit card processor were depositing more cash than last month. All was right in the world of automation. It was a beautiful sunny day, and I closed my laptop with a smile. For an all-you-can-eat buffet breakfast with coffee and orange juice, I paid $4 U.S. The Indian outsourcers cost between $4–10 U.S. per hour. My domestic outsourcers are paid on performance or when product ships. This creates a curious business phenomenon: Negative cash flow is impossible. Fun things happen when you earn dollars, live on pesos, and compensate in rupees, but that’s just the beginning. (I love this story. It is here just because I love it.) Eliminate before you delegate. Never automate something that can be eliminated, and never delegate something that can be automated or streamlined. It is tempting to immediately point the finger at someone else and huff and puff, but most beginner bosses repeat the same mistakes I made. 1. I accepted the first person the firm provided and made no special requests at the outset. 2. I gave imprecise directions. 3. I gave him a license to waste time. 4. I set the deadline a week in advance. 5. I gave him too many tasks and didn’t set an order of importance. As to methods there may be a million and then some, but principles are few. The man who grasps principles can successfully select his own methods. The man who tries methods, ignoring principles, is sure to have trouble. —RALPH WALDO EMERSON His business model is more elegant than that. Here is just one revenue stream: 1. A prospective customer sees his Pay-Per-Click (PPC) advertising on Google or other search engines and clicks through to his site, www.prosoundeffects.com. 2. The prospect orders a product for $325 (the average purchase price, though prices range from $29–7,500) on a Yahoo shopping cart, and a PDF with all their billing and shipping information is automatically e-mailed to Doug. 3. Three times a week, Doug presses a single button in the Yahoo management page to charge all his customers’ credit cards and put cash in his bank account. Then he saves the PDFs as Excel purchase orders and e-mails the purchase orders to the manufacturers of the CD libraries. Those companies mail the products to Doug’s customers—this is called drop-shipping—and Doug pays the manufacturers as little as 45% of the retail price of the products up to 90 days later (net-90 terms). This chapter is not for people who want to run businesses but for those who want to own businesses and spend no time on them. People can’t believe that most of the ultrasuccessful companies in the world do not manufacture their own products, answer their own phones, ship their own products, or service their own customers. There are hundreds of companies that exist to pretend to work for someone else and handle these functions, providing rentable infrastructure to anyone who knows where to find them. Before we create this virtual architecture, however, we need a product to sell. If you own a service business, this section will help you convert expertise into a downloadable or shippable good to escape the limits of a per-hour-based model. If starting from scratch, ignore service businesses for now, as constant customer contact makes absence difficult. To narrow the field further, our target product can’t take more than $500 to test, it has to lend itself to automation within four weeks, and—when up and running—it can’t require more than one day per week of management. Our goal is simple: to create an automated vehicle for generating cash without consuming time. That’s it.22 I will call this vehicle a “muse” whenever possible to separate it from the ambiguous term “business,” which can refer to a lemonade stand or a Fortune 10 oil conglomerate—our objective is more limited and thus requires a more precise label. So first things first: cash flow and time. With these two currencies, all other things are possible. Without them, nothing is possible. (I think there is a third one, your network) Here’s how you do it in the fewest number of steps. Step One: Pick an Affordably Reachable Niche Market The 4-Hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich (Expanded and Updated) Creating demand is hard. Filling demand is much easier. Don’t create a product, then seek someone to sell it to. Find a market—define your customers—then find or develop a product for them. Ask yourself the following questions to find profitable niches. 1. Which social, industry, and professional groups do you belong to, have you belonged to, or do you understand, Which of the groups you identified have their own magazines? Step Two: Brainstorm (Do Not Invest In) Products Pick the two markets that you are most familiar with that have their own magazines with full-page advertising that costs less than $5,000. There should be no fewer than 15,000 readers. This is the fun part. Now we get to brainstorm or find products with these two markets in mind. The goal is come up with well-formed product ideas and spend nothing; The Main Benefit Should Be Encapsulated in One Sentence. People can dislike you—and you often sell more by offending some—but they should never misunderstand you. The main benefit of your product should be explainable in one sentence or phrase. It Should Cost the Customer $50–200. The bulk of companies set prices in the midrange, and that is where the most competition is. Pricing low is shortsighted, because someone else is always willing to sacrifice more profit margin and drive you both bankrupt. Besides perceived value, there are three main benefits to creating a premium, high-end image and charging more than the competition. Higher pricing means that we can sell fewer units—and thus manage fewer customers—and fulfill our dreamlines. It’s faster. Higher pricing attracts lower-maintenance customers (better credit, fewer complaints/questions, fewer returns, etc.). It’s less headache. This is HUGE. Higher pricing also creates higher profit margins. It’s safer. I personally aim for an 8–10x markup, which means a $100 product can’t cost me more than $10–12.50.27 I have found that a price range of $50–200 per sale provides the most profit for the least customer service hassle. Price high and then justify. It Should Take No More Than 3 to 4 Weeks to Manufacture. This is critically important for keeping costs low and adapting to sales demand without stockpiling product in advance. It Should Be Fully Explainable in a Good Online FAQ. Understanding these criteria, a question remains: “How does one obtain a good muse product that satisfies them?” There are three options we’ll cover in ascending order of recommendation. Option One: Resell a Product Purchasing an existing product at wholesale and reselling it is the easiest route but also the least profitable. It is the fastest to set up but the fastest to die off due to price competition with other resellers. The profitable life span of each product is short unless an exclusivity agreement prevents others from selling it. Reselling is, however, an excellent option for secondary back-end28 products that can be sold to existing customers or cross-sold29 to new customers online or on the phone. Option Two: License a Product Option Three: Create a Product Creating a product is not complicated. “Create” sounds more involved than it actually is. If the idea is a hard product—an invention—it is possible to hire mechanical engineers or industrial designers on www.elance.com to develop a prototype based on your description of its function and appearance, which is then taken to a contract manufacturer. If you find a generic or stock product made by a contract manufacturer that can be re-purposed or positioned for a special market, it’s even easier: Have them manufacture it, stick a custom label on it for you, and presto—new product. This latter example is often referred to as “private labeling.” Information products are low-cost, fast to manufacture, and time-consuming for competitors to duplicate. Consider that the top-selling non-information infomercial products—whether exercise equipment or supplements—have a useful life span of two to four months before imitators flood the market. Information, on the other hand, is too time-consuming for most knockoff artists to bother with when there are easier products to replicate. It’s easier to circumvent a patent than to paraphrase an entire course to avoid copyright infringement. Three of the most successful television products of all time—all of which have spent more than 300 weeks on the infomercial top-10 bestseller lists—reflect the competitive and profit margin advantage of information products. No Down Payment (Carlton Sheets) Attacking Anxiety and Depression (Lucinda Bassett) Personal Power (Tony Robbins If you aren’t an expert, don’t sweat it. First, “expert” in the context of selling product means that you know more about the topic than the purchaser. No more. It is not necessary to be the best—just better than a small target number of your prospective customers. Second, expert status can be created in less than four weeks if you understand basic credibility indicators. 1. How can you tailor a general skill for your market—what I call “niching down”—or add to what is being sold successfully in your target magazines? Think narrow and deep rather than broad. 2. What skills are you interested in that you—and others in your markets—would pay to learn? Become an expert in this skill for yourself and then create a product to teach the same. If you need help or want to speed up the process, consider the next question. 3. What experts could you interview and record to create a sellable audio CD? These people do not need to be the best, but just better than most. Offer them a digital master copy of the interview to do with or sell as they like (this is often enough) and/or offer them a small up-front or ongoing royalty payment. Use Skype.com with HotRecorder (more on these and related tools in Tools and Tricks) to record these conversations directly to your PC and send the mp3 file to an online transcription service. 4. Do you have a failure-to-success story that could be turned into a how-to product for others? Consider problems you’ve overcome in the past, both professional and personal. The Expert Builder: How to Become a Top Expert in 4 Weeks How, then, do we go about acquiring credibility indicators in the least time possible? 1. Join two or three related trade organizations with official-sounding names. 2. Read the three top-selling books on your topic (search historical New York Times bestseller lists online) and summarize each on one page. 3. Give one free one-to-three-hour seminar at the closest well-known university, using posters to advertise. 4. Optional: Offer to write one or two articles for trade magazines related to your topics, citing what you have accomplished in steps 1 and 3 for credibility. 5. Join ProfNet, which is a service that journalists use to find experts to quote for articles Income Autopilot II The moral is that intuition and experience are poor predictors of which products and businesses will be profitable. To get an accurate indicator of commercial viability, don’t ask people if they would buy—ask them to buy. Step Three: Micro-Test Your Products Micro-testing involves using inexpensive advertisements to test consumer response to a product prior to manufacturing. The basic test process consists of three parts, each of which is covered in this chapter. Best: Look at the competition and create a more-compelling offer on a basic one-to-three-page website (one to three hours). Test: Test the offer using short Google Adwords advertising campaigns (three hours to set up and five days of passive observation). Divest or Invest: Cut losses with losers and manufacture the winner(s) for sales rollout. Sherwood first tests his concept with a 72-hour eBay auction that includes his advertising text. He sets the “reserve” (the lowest price he’ll accept) for one shirt at $50 and cancels the auction last minute to avoid legal issues since he doesn’t have product to ship. He has received bids up to $75 and decides to move to the next phase of testing. Johanna doesn’t feel comfortable with the apparent deception and skips this preliminary testing. Sherwood’s cost: <$5. Both register domain names for their soon-to-be one-page sites using the cheap domain registrar www.domainsinseconds.com. Sherwood chooses www.shirtsfromfrance.com and Johanna chooses www.yogaclimber.com. For additional domain names, Johanna uses www.domainsinseconds.com. Cost to both: <$20. Sherwood uses www.weebly.com to create his one-page site advertisement and then creates two additional pages using the form builder www.wufoo.com. If someone clicks on the “purchase” button at the bottom of the first page, it takes them to a second page with pricing, shipping and handling,43 and basic contact fields to fill out (including e-mail and phone). If the visitor presses “continue with order,” it takes them to a page that states, “Unfortunately, we are currently on back order but will contact you as soon as we have product in stock. Thank you for your patience.” This structure allows him to test the first-page ad and his pricing separately. If someone gets to the last page, it is considered an order. Johanna is not comfortable with “dry testing,” as Sherwood’s approach is known, even though it is legal if the billing data isn’t captured. She instead uses the same two services to create a single webpage with the content of her one-page ad and an e-mail sign-up for a free “top 10 tips” list for using yoga for rock climbing. She will consider 60% of the sign-ups as hypothetical orders. Cost to both: <$0. Both set up simple Google Adwords campaigns with 50–100 search terms to simultaneously test headlines while driving traffic to their pages. Their daily budget limits are set at $50 per day Sherwood will use Google’s free analytical tools to track “orders” and page abandonment rates—what percentage of visitors leave the site from which pages. Johanna will use www.wufoo.com to track e-mail sign-ups on this small testing scale. Johanna has done well. The traffic wasn’t enough to make the test stand up to statistical scrutiny, but she spent about $200 on PPC and got 14 sign-ups for a free 10-tip report. If she assumes 60% would purchase, that means 8.4 people x $75 profit per DVD = $630 in hypothetical total profit. This is also not taking into account the potential lifetime value of each customer. The results of her small test are no guarantee of future success, but the indications are positive enough that she decides to set up a Yahoo Store for $99 per month and a small per-transaction fee. Her credit isn’t excellent, so she will opt to use www.paypal.com to accept credit cards online instead of approaching her bank for a merchant account.46 She e-mails the 10-tip report to those who signed up and asks for their feedback and recommendations for content on the DVD. Ten days later, she has a first attempt at the DVD ready to ship and her store is online. Her sales to the original sign-ups cover costs of production and she is soon selling a respectable 10 DVDs per week ($750 profit) via Google Adwords. She plans to test advertising in niche magazines and blogs and now needs to create an automation architecture to remove herself from the equation. 1. Market Selection 2. Product Brainstorm 3. Micro-Testing 4. Rollout and Automation Income Autopilot III MBA—MANAGEMENT BY ABSENCE Once you have a product that sells, it’s time to design a self-correcting business architecture that runs..... The 4-Hour Workweek: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich (Expanded and Updated) The Willpower Instinct: How Self-Control Works, Why It Matters, and What You Can Do To Get More of It by Ph.D., Kelly McGonigal